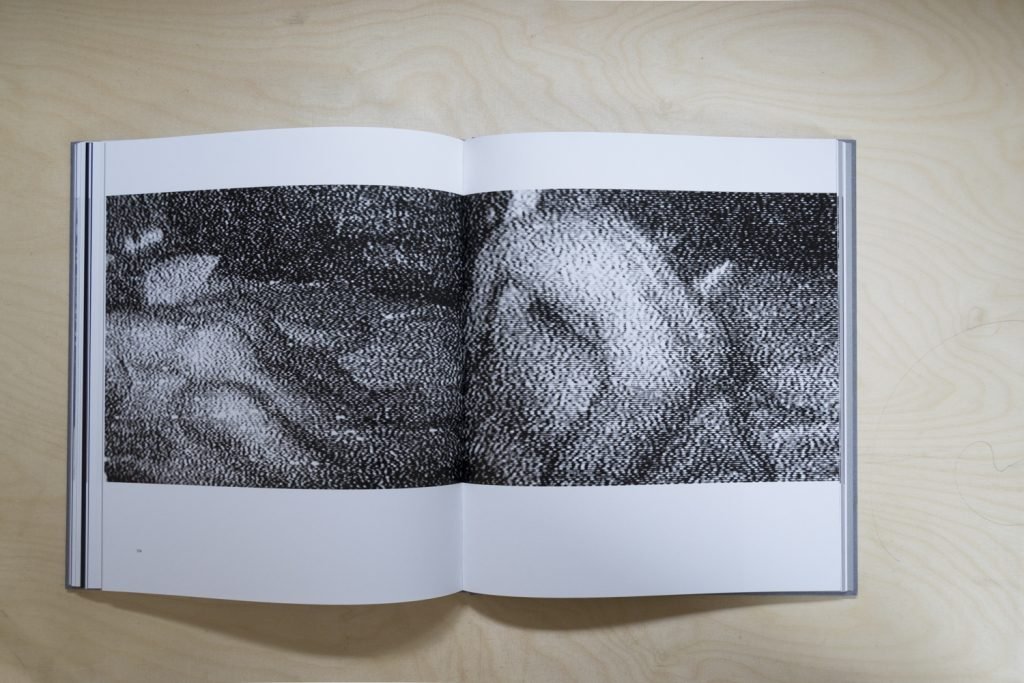

“Inevitably linked with the moment of climax, there is a minor rupture suggestive of death; and conversely the idea of death may play a part in setting sensuality in motion.”

Georges Bataille

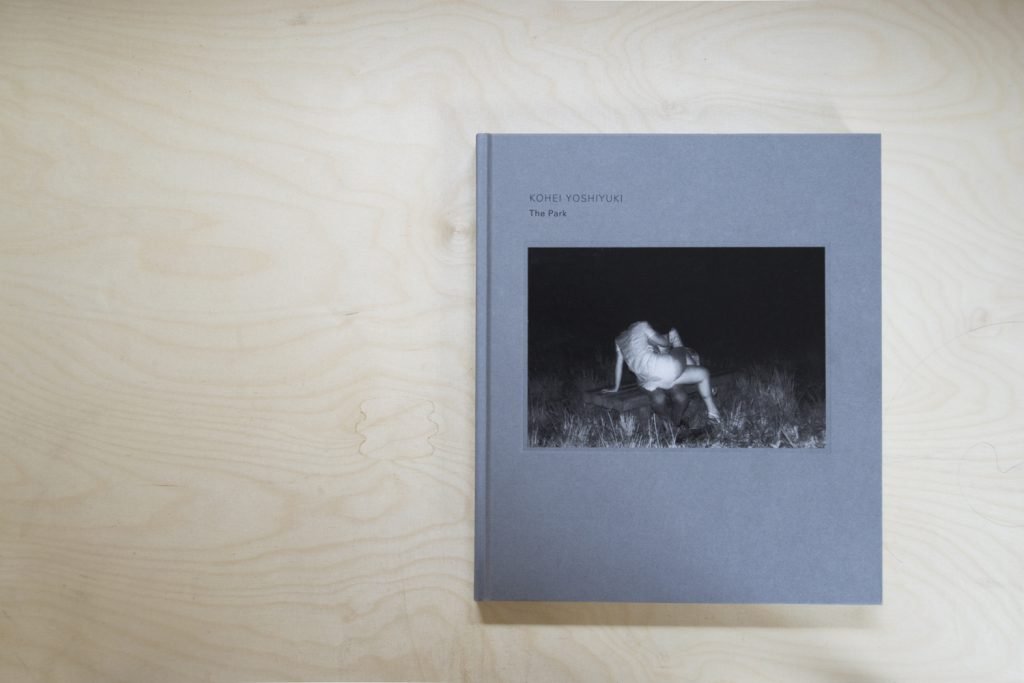

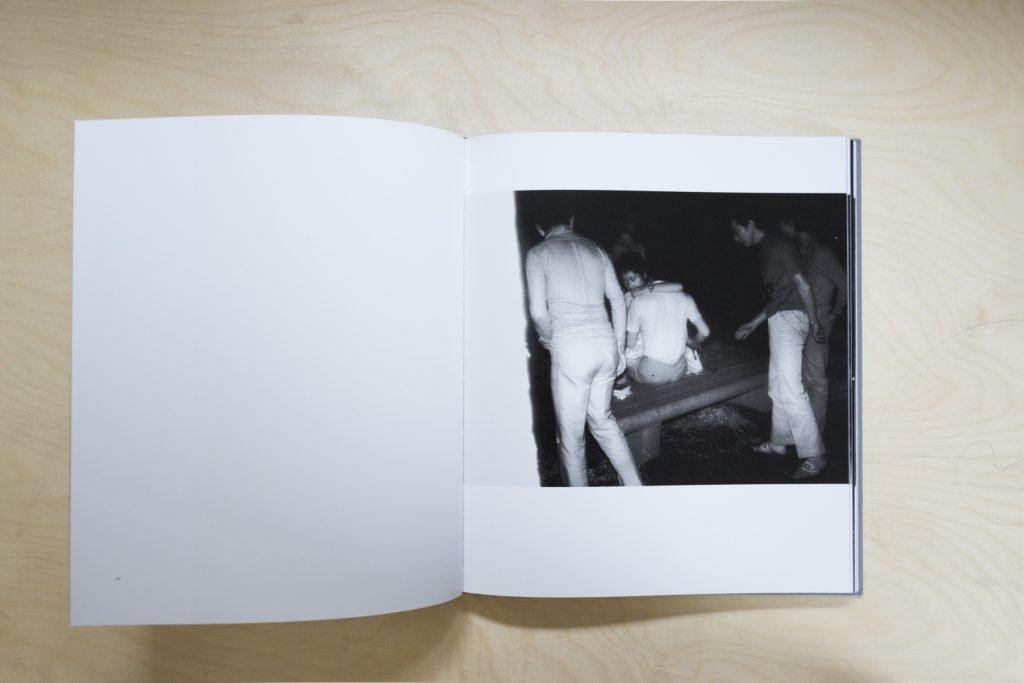

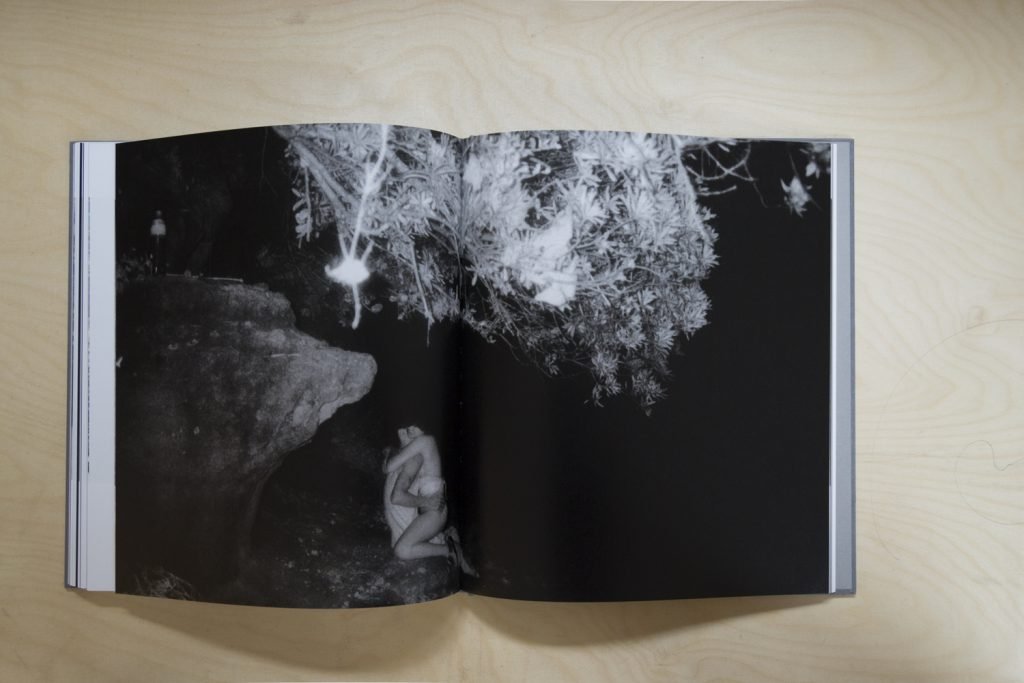

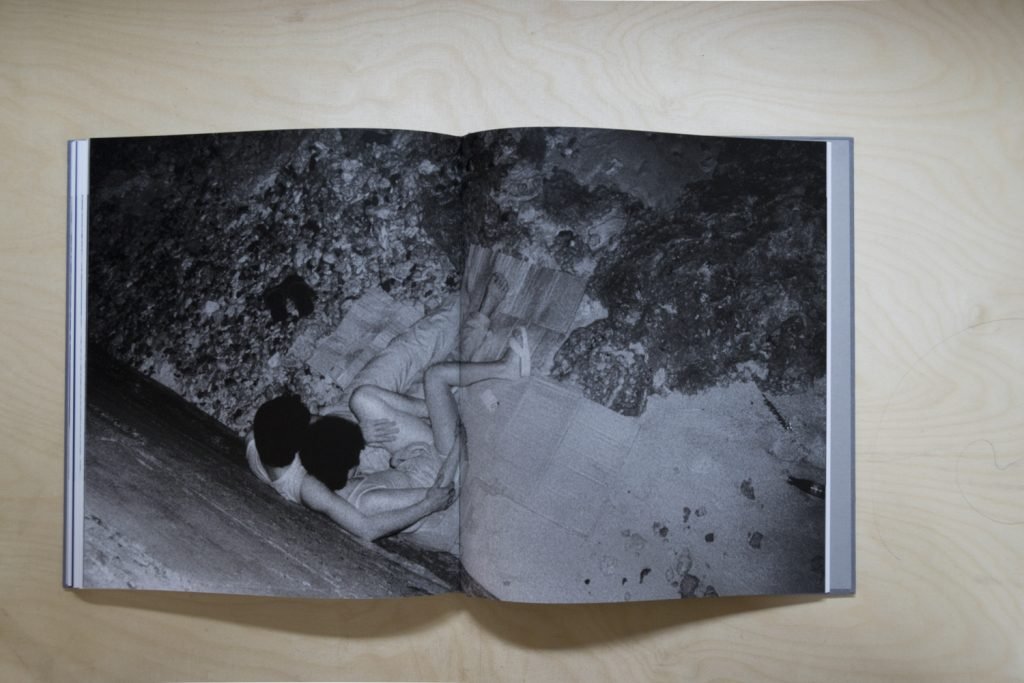

During the 1970s, Kohei Yoshiyuki spent many evenings alongside the night-watchers in Tokyo’s Chuo Park documenting their Peeping Toms activity. Having become their friend and accompanying them in their ambushes to look at young couples in canoes (and more), Yoshiyuki has brought to light a turbid and draining tale in which the play of the parts is reversed to transform the same stalkers into the object of observation.

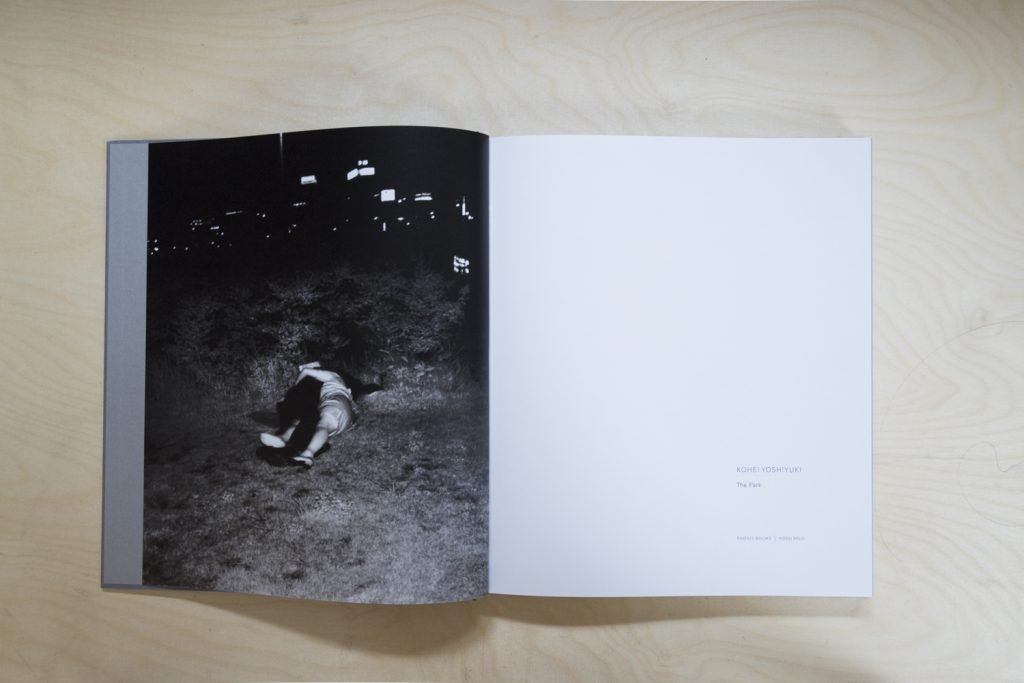

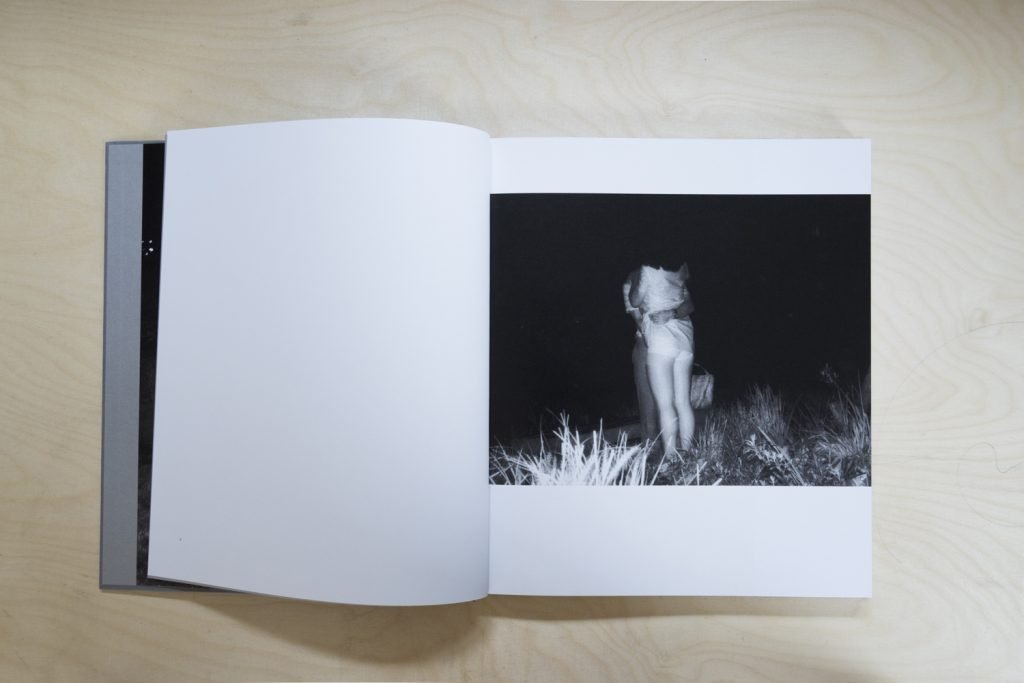

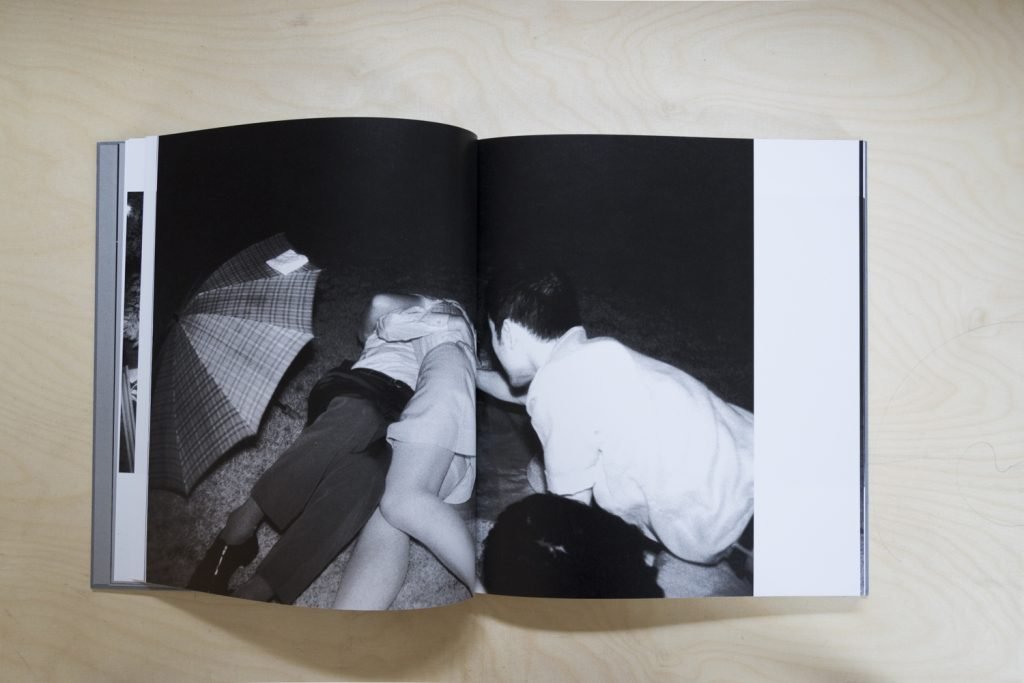

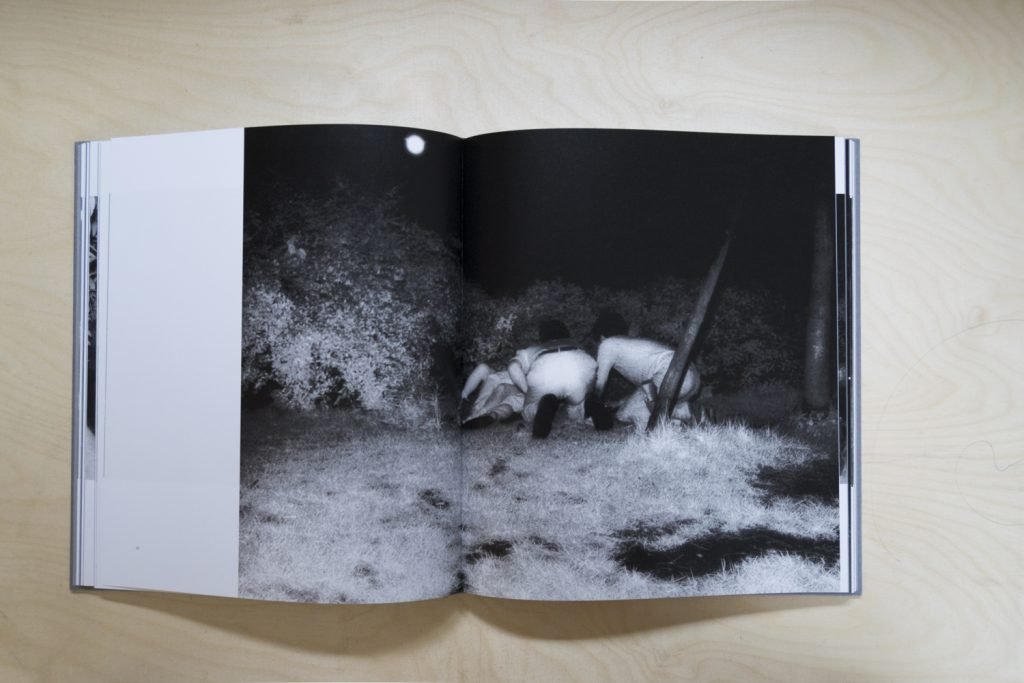

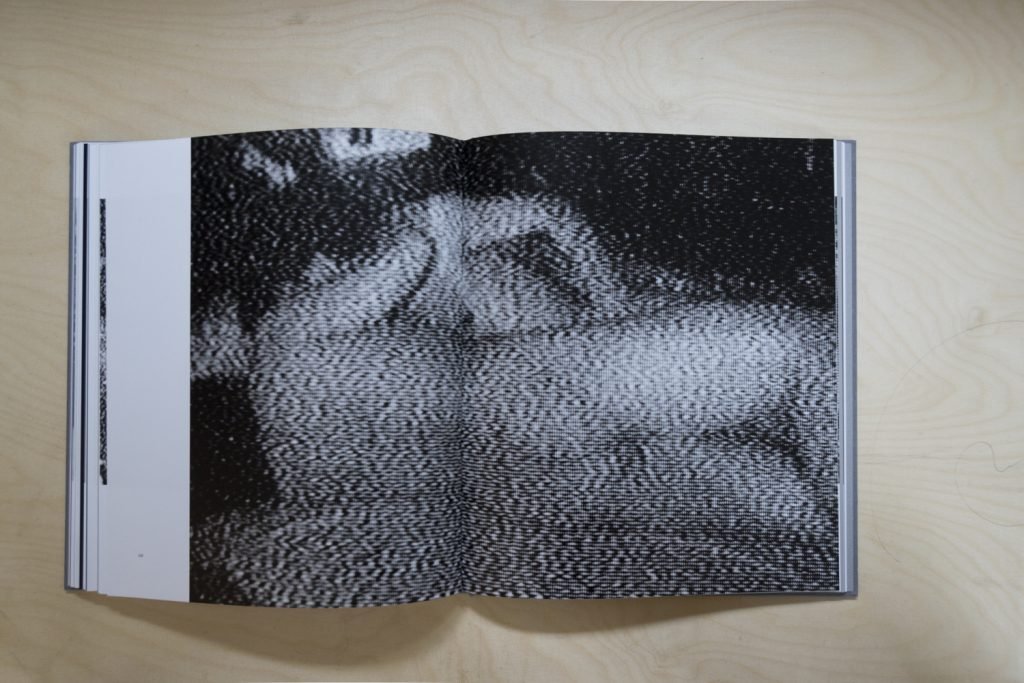

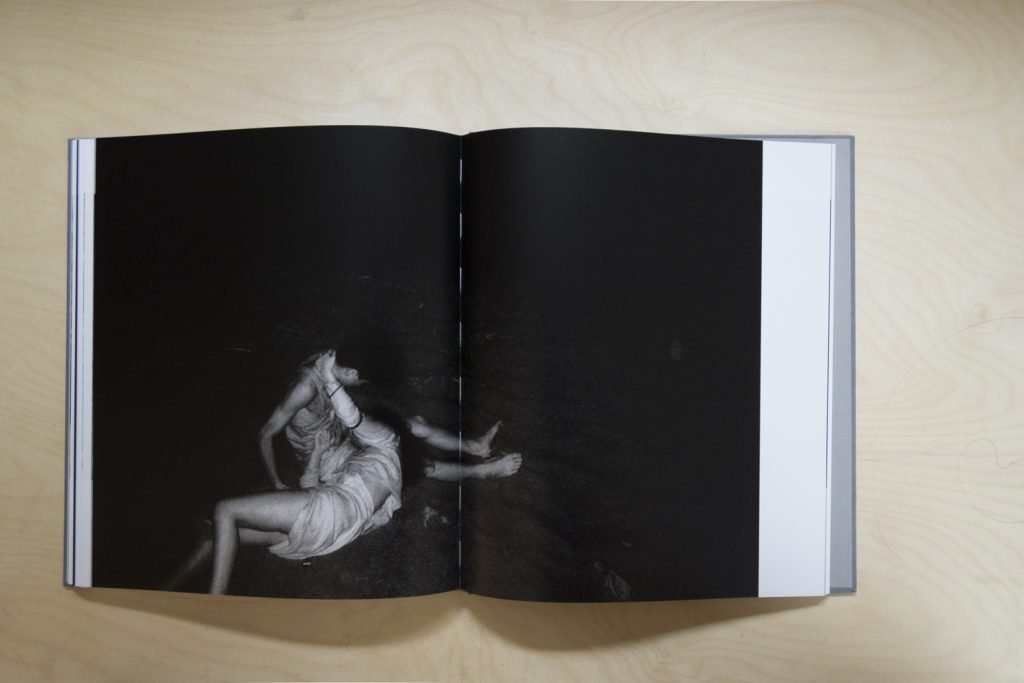

Revealing the visceral and amused thrill of voyeurism, Yoshiyuki puts us in front of a secret universe in which sexual freedom and fetish, privacy and surveillance and the dark and uncomfortable spaces in which everyone mix, become useful elements to outline a territory of experimentation and linguistic ambiguity.

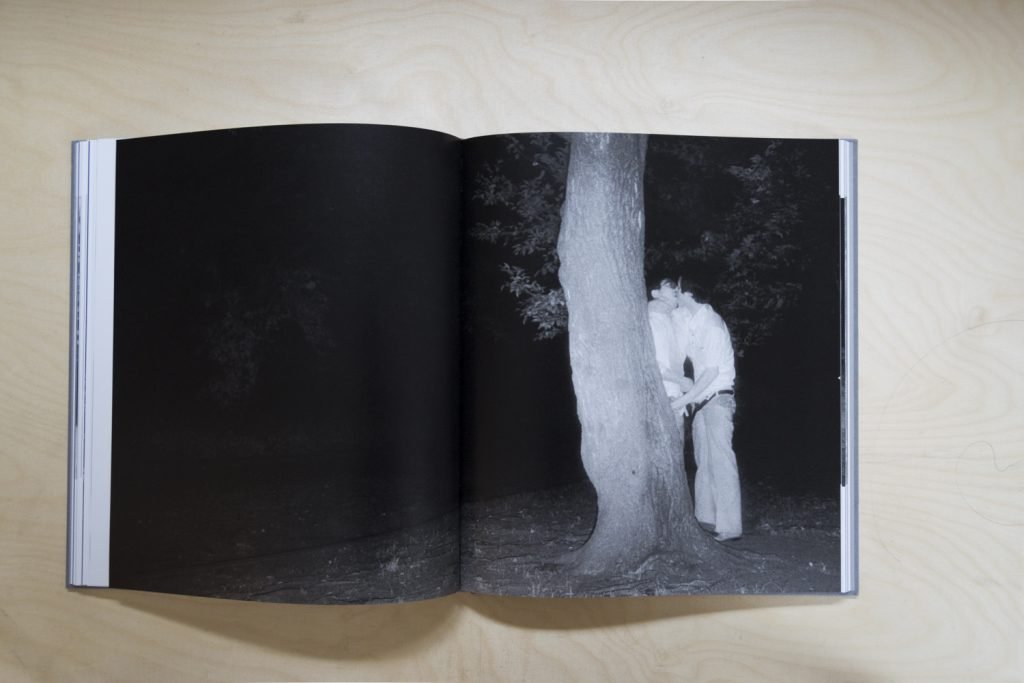

Found and searched within a darkness that hidden and swallows, the images of Kohei Yoshiyuki show surreal scenes; fully dressed men staring at couples – both hetero and homosexual – who happily tighten themselves in ignorance of their audience. Voyeurs with unbuttoned trousers getting so close to the lovers they could touch them; figures gathered in the shadow waiting carefully like predators. Rare, exciting, difficult images that raise a powerful critical issue today as it was in the 70s.

Yoshiyuki introduced the series for the first time in a 1972 issue of Shukan Shincho, a popular Japanese magazine that freely explored issues considered taboo in the country. At that time, premarital sex and homosexuality were widely criticized in Japan and young couples frequently lived with their parents until marriage. Parks like Chuo in Tokyo have offered a clandestine place where couples could get to know each other freely by temporarily escaping from the disciplinary forms imposed by a legislature; recalled by the legal scholar Katherine Biber in her 2015 essay “Peeping: Open Justice and Law’s Voyeurs “: it was “illegal to engage in public indecency. … It was illegal to have sex in the park, it was illegal to watch couples having sex in the park, it was illegal to photograph them and it was also illegal to show or distribute those photographs.” (1970).

Also provocatively playing on the illicit nature of the project, the publication of the images by Yoshiyuki (1972) had and keeps on having a great success, making this author and this project an object of worship. If Yoshiyuki’s photos had the audacity to exploit timeless human impulses, vulnerabilities and perversions, they also have the merit of having brought to light one of the many aspects of human nature, which in the incessant search for a pleasure and a sense does not cease to experiment and construct imaginaries.