Giangiacomo Cirla: Hello Sheida, I’m pleased to start this conversation with you since I’m sure I can address various issues that I am interested in investigating in a thorough way given your personal preparation and experience. First of all, since you took your first degree in photography at the age of 22 and an MFA degree at the age of 25 in photography, I am interested in asking you how you approached the practice of photography and if it is right to think that by observing your path, you had clear ideas very early on the choice of the most suitable medium to communicate.

Sheida Soleimani: When I started taking photographs as a teenager, I would divide my time between dressing up my friends and photographing them in cemeteries and abandoned factories, or, I would take photos of nature and landscapes. At that time, I viewed the camera as a tool that could either create an alternate reality, or one that could document an existing one. When I started college, I started learning more about the history of the medium, and how the genre of documentary imagery was male driven, and oftentimes exploitative of the subject matter, and I wanted to push back against that. I decided to continue upon my thread of creating scenes and images, but changed the content to create narratives that told stories about my family history (a little less teenage angst/ cemetery photos!). When I was 22, for my last year of college, I built a room in the woods at my family’s home in Ohio, and would stage scenes to photograph in the space. It was important for me to use the medium of photography as a document of the scene, as a sort of evidence, just how photographs have historically been used to ‘tell truths’. When I started grad school at 23, I knew I wanted to continue using photography as a means to tell my stories, but I wanted to play with contemporary issues and aesthetics- thinking a lot about image sharing on social media, advertising, food photography, and creating a larger global dialogue- not just around my own family, but more about the political issues at large in Iran and the Middle East. Photo seemed like the perfect medium for this- paintings, prints, drawings can create representations of things, and can be stylized, but even a photo-realistic painting or drawing is a degree away from the ‘real’ object. Photo can take the ‘realness’ of something and fuck it up…make it identifiable, but invert its purpose. We’re conditioned to read images and objects to mean specific things or to have specific identities: photography can challenge how we read ‘real’ images and how we identify objects, places, bodies. In that sense, I think photography is the perfect medium for my messages and narratives because so much of the content of my work is about questioning how we receive information and how we are taught to absorb it.

GC: I absolutely agree, I think the contemporary image must necessarily reason on the real nature of visual language. The ability to compose narratives through fractions of reality that become autonomous bearers of meaning, becoming truthful as visual evidence, is on the one hand very interesting as regards the possibility of making objective something that instead arises from subjectivity, as an artistic project, on the other hand allows us to reflect on how deceptive an image can be, emphasizing how they must always be questioned. What is your opinion on this, why do you think visual language is understood as truthful much more than verbal or nonverbal?

SS: I think society’s relationship to truth has to do with how the law has defined forms of evidence; the four types of evidence often recognized by courts include demonstrative, real, testimonial and documentary. Testimonial and verbal evidence is viewed by the court to be the simplest type of evidence, and is typically in the form of an eyewitness statement. Documentary evidence, including photographic imagery is most often considered ‘real’ evidence, and provides a visual image as a form of proof of testimony. Even though a photographic image can be colored by biases, or can be doctored, this is less evident to the public as we’re not often taught to question the authenticity of an image.

GC: Moreover, today we live in an era of hyper-production of images and therefore of greater possibilities to compose new narratives through visual elements borrowed from their original context. In this sense, your work is the perfect representation of how powerful and impressive can be an expression created by recomposing internal elements to ensure a new reading. How do you articulate your practice, how do you build your images?

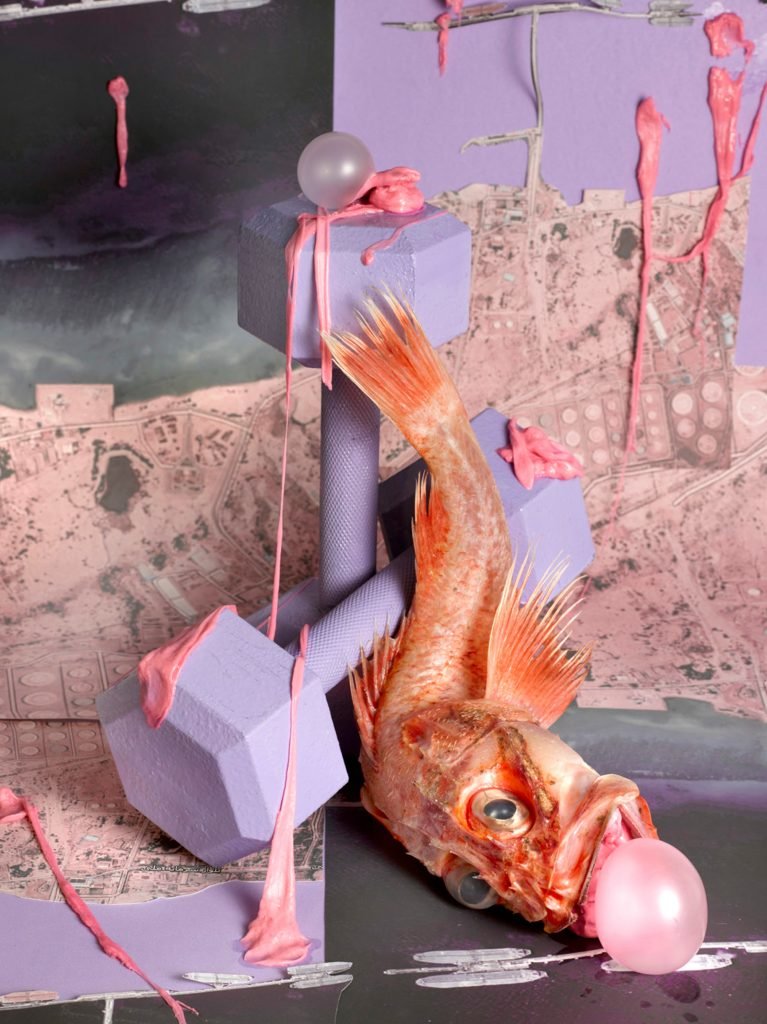

SS: Research is central to my practice, and is a big part of how I choose the images I decide to work with and build upon. I usually begin by sketching out my ideas a few times, and then printing images pulled from the web that correspond to specific aspects of my research and allow me to think of the piece I’m working on as a kind of story, which can be read through interactive, sustained engagement with the piece. The source images are then chopped, screwed, and cut to create cyborg-like entities; re-animating how popular media fragments and disembodies stories and events. These images are overlaid onto three-dimensional objects, forming a tabletop or larger stage set. I also consider and draw upon the lighting techniques of advertising, using strobe lights that add a certain kind of lurid theatricality to the mix.

GC: this methodology greatly increases the possibilities, it’s like inventing new words that can express the concept with greater immediacy.

The images resulting from this composition process convey your perspectives on historical and contemporary socio-political events. In this message, does the origin of the individual components also carry a message?

SS: Absolutely. Each individual symbol, image, and object has a message and history embedded in it, and works with the other symbols and images to create a complex narrative. To decode the meaning of each photograph the symbols work together, similar to a map key, giving clues as to what the entire message and story is.

GC: Your work stems from family experiences involving the total absence of freedom of thought and expression caused by extreme methods of control. I think that the decision to structure an artistic practice, which openly places itself in a context outside of a comfort zone, is a direct response to an attempt at deprivation…

SS: In the absence of verbal language, visual language has the ability to cross borders. The need to code political messages and ideologies in Iranian art became status quo after shortly after the 1979 revolution, with many intellectuals and artists having been made into examples by the regime of how outspoken viewpoints would not be tolerated. By looking at contemporary Iran, as well as the history of its tumultuous interactions with the West, we can begin to understand not only the severity of censorship, but also how art and culture have adapted to the suppression of free speech and the limitations on expression by reactionary regime In brief, the government has handicapped artists by limiting what they can say or show. Intellectuals, writers, poets, satirists, and visual artists are pushing back, using symbol-rich work to get their message across in a more veiled fashion. Oftentimes , the West criticizes Iranian artists for not being direct enough in their visual and verbal language, expressing difficulty in deciphering an inexplicit symbolic language. Many Iranians have seen and felt the consequences of being direct, and not many are willing to risk their lives. However, even with the use of symbolism, there are still consequences to pay. Iranian artists are still forced to use symbols as indirect expressions of their ideologies. Artists of the Iranian diaspora often use symbolic coding in a similar way, though often far more directly. For members of the diaspora like myself, there is no imminent threat of imprisonment or death, but speaking out against the regime in any way can result in the threat of exile. Within the diaspora, this threat has become a divide and raises a question for immigrants, as well as first and second generational individuals: how explicit should you be about your politics, and what repercussions can your opinions and art have?

GC: Does anger play a role?

SS: Absolutely. Anger drives my work. Growing up in America, I learned quickly that American’s were not aware of the severity of injustices in Iran, and that lack of education always has made me angry. The primary source of anger, however, has always been with the Iranian government for abusing its citizens. Creating awareness about these human rights violations fuels the urgency of my practice in hopes that visibility can create momentum within communities who would have otherwise been ignorant to this history.

GC: In this sense, the fact that you are an artist of the diaspora, moreover residing in the United States, charges you with duties, among which perhaps the greatest is to create a direct and clear attack, readable by many, just to disclose as much as possible the information in your possession. How much do you feel this duty and how demanding is it with your work to represent many voices who are not lucky enough to be able to express themselves freely?

SS: Having spent my entire life as a witness to the Iranian regime’s suppression of free speech, it’s hard for me to imagine a future of freedom. Violence and death continue to be the chief methods by which the government eliminates dissenting voices, and this power has only been extended in recent decades as the regime actively thwarts its citizens’ efforts to disseminate their stories to the outside world. For individuals such as myself, I believe it is the job of the diaspora to be the voice that communicates what citizens within Iran cannot. Trauma is often shared between generations of the diaspora through familial histories, but contemporary generations may not always understand the urgency, or what is at stake. Just like ‘morse code’, or early pictograms that have become modes of communication when direct speech has not been possible, symbol based lexicons [JS1] within artworks can prove to be useful yet: leaving a trace of/communicating our history, while urging audiences to learn about how they participate in modern society.

GC: Speaking instead of the context in which you currently are, don’t you think that perhaps, not having real knowledge of an absence of freedom, in a place like the United States (and not only) is often taken for granted and therefore there are fewer and fewer artists who openly criticize the context through their work, encouraging an attitude of questioning?

SS: Absolutely. If individuals don’t feel like their own freedoms are threatened, they are less likely to be willing to discuss the freedoms of others.

GC: Talking about the absence of freedom and wanting to analyze it in its application in the field of communication, I would like to come back for a moment to talk about your research methodology. You told me that research is central in your practice and thinking about your series “To Oblivion” of 2016 I realize how complicated it can be to get to the kind of documentation your work needs. Can you tell me about it?

SS: For this series, I started conversations with human rights lawyers in Iran to learn and find out more information about women who had been wrongfully executed by the Iranian government. Through my communications with families, lawyers, and activists, I was able to get access to letters, execution records, and photographs to create portraits of these disappeared women.

GC: I suppose that communication, especially with families and activists, is not easy and immediate. How does the exchange of documents take place and how long does this process take? Furthermore,the sources are at risk by residing in Iran. There must be a lot of trust at the base…

SS: The process takes weeks, months, and has sometimes been ongoing for years- keeping in regular touch with individuals and families has been a large part of creating trusting relationships. While creating ‘To Oblivion’, a large part of my conversations included sharing the images I was making, as well as discussing my own story and familial background with the families of each victim. The basis of my relationships with each individual was founded on my promise that their identities would be protected and not shared, and that I would use my voice and work as a medium to project their thoughts and opinions.

GC: Looking at “The Oblivion” I was particularly struck by the reference to Albert Bandura and the “Bobo Doll” experiment…

SS: Through referencing the Bandura Bobo Doll Experiment on Observational Learning, the forms of each sculpture take cues from the ‘Bobo Doll’. The experiment, a series of tests conducted by Albert Bandura in 1961, studied children’s behavior after watching an adult model act aggressively towards a Bobo Doll; the most notable experiment measured the children’s behavior after seeing the model get rewarded, get punished, or experience no consequence for beating up the doll. Creating these sculptures as forms that are analogous to the Bobo Doll suggests that through carrying out public executions, the Iranian Government endorses aggression against women throughout Iranian society.

GC: We talked about impositions, lack of freedom and anger. I would think of a kind of work that embraces the aesthetics of tragedy and horror, but instead, looking at your work, we are faced with something totally different. What role does irony play in your work?

SS: We’re accustomed to media and world news being violent in both content and imagery, and that often makes us push information away. Through using seduction, irony, and humor, viewers first pay attention to an image based on its aesthetic qualities before fully understanding what it is about (like a Trojan horse). With this gesture, I hope to trick viewers into contending with the content after getting past their initial attraction to the photographs.

GC: From this point of view your work reminds me of Martha Rosler’s “War Home” collages, capable of using an advertising aesthetic conveyed by an immediate communication offered by a medium like Life magazine. Do you find yourself in that? What are your influences?

SS: Yes- I love her ‘War Home’ series! I also find inspiration in the works of Jack Smith, Hannah Hoch, Yamini Nayar, Liz Cohen, Hal Fischer, Gauri Gill, Mickalene Thomas, and Samuel Fosso.

Sheida Soleimani (born 1990) is an Iranian-American multimedia artist, activist, and professor.Her works have generated conversations in the field of ‘constructed’ tableau photography, as well as the intersections of art and protest.

Soleimani’s work highlights the relationships between powerful political people, groups, governments, and corporations, in order to raise questions from the viewer. The themes of her work are topics not often discussed in the West, for example, highlighting the women executed in Iran, and the relationship between power, exploitation and oil, among others. The work is often displayed as a photograph or video of a staged image, Soleimani uses various materials in the work including, soft sculpture “dolls”, photography, props, masks, and cut-outs of digital prints.

Soleimani is currently an Assistant Professor of Studio Art at Brandeis University. She previously taught at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).