In the introduction to the book The Museological Unconscious: Communal (Post) Modernism in Russia, Victor Tupitsyn notes that, when reviewing the history of any sort of “alternative”, researchers usually start with the description of the phenomenon that gave an impulse to its formation (tradition/avant-garde dichotomy, for instance) [1].

The author puts in question the relevance of the analysis of these notions solely as oppositions, since both of them, as a rule, have a common audience. In the case of the Soviet official and non-official art, in Tupitsyn’s opinion, the common audience is communal perception. Indeed, typical Soviet communal dwelling was one of the instruments of the government for implementing its policy of depersonalization. On the other hand, various forms of existence of non-official culture (jokes, samizdat / self-published books, etc.) transformed into legendary “kitchen talk”’. And it was the communal reality that became the base for such artistic phenomenon as Moscow Conceptualism. Communal discourse also updated the question of physicality and its functioning, as well as the interrelation of the social and the individual within it. The structure of personal space got into the field of attention of Kharkiv photographers in the 1970s-1980s, including work of Roman Pyatkovka (b. 1955).

Roman began his creative activity in the mid-late 1980s, though his entering the world of photography started earlier, and it wasn’t a one-step process. Roman studied at Electric Power Engineering Faculty of the Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute. The prospect of working in that sphere didn’t really attract the young man. So he took a course in production for lighting designers in the Karpenko-Karyi Kyiv State Institute of Theatrical Arts (today known as Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Kary Theatre, Cinema and Television University). After completing the course he became the leading lighting designer in the Young Spectator’s Theatre in Kharkiv. Apart from such a radical change of profession which, in its turn, changed the environment the artist lived in, Pyatkovka couldn’t but make friends with the people belonging to the art scene of Kharkiv who regularly gathered in “In Garshina” and “Buchenwald” cafes. There he met such already famous artists as Boris Mikhailov and Oleg Maliovany. Under their influence, yet not leaving the job in the theatre, Roman took his first steps in photography. Later, he fully committed himself to this sphere by becoming a laboratory assistant at art combine.

Both Mikhailov and Maliovany played a very significant role in the formation of the young artist. Just like in most cases with other members of Kharkiv School of Photography, informal discussions co-called “showing” the pictures to each other, were one of the crucial catalysts of creative experiments. Maliovany as one of the most technically aware photographers in Kharkiv at that time (especially when it came to using colour), shared his experience in working with materials. Interaction with Mikhailov formed concept-oriented approach to creative work in general. The importance of the latter makes itself felt in the way Pyatkovka continuously declares that the “picture” doesn’t interest him since he always thinks in projects.

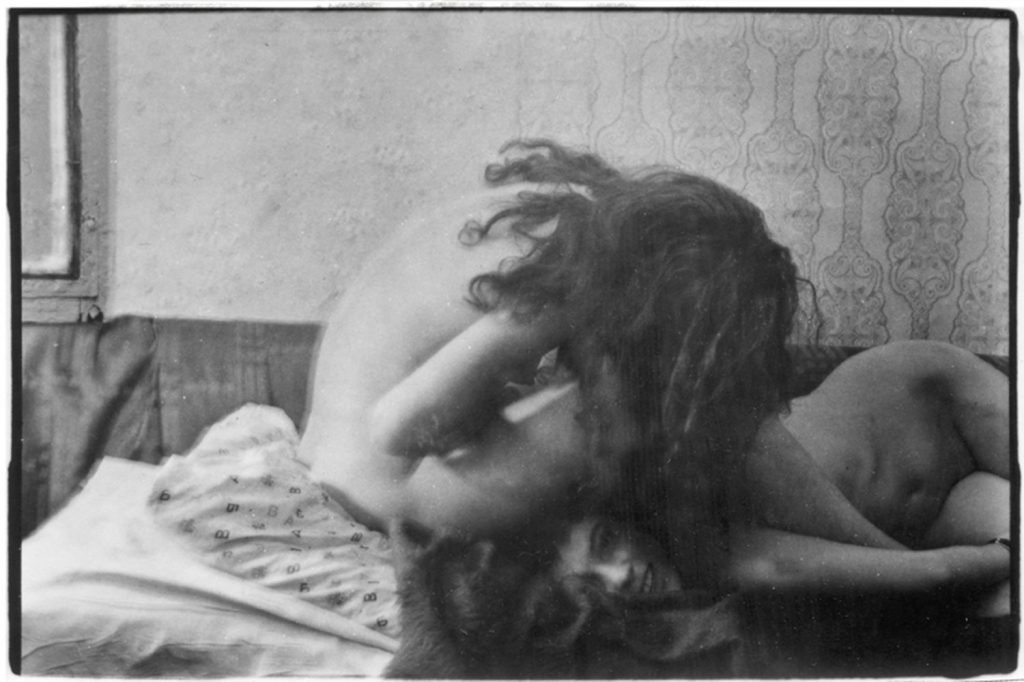

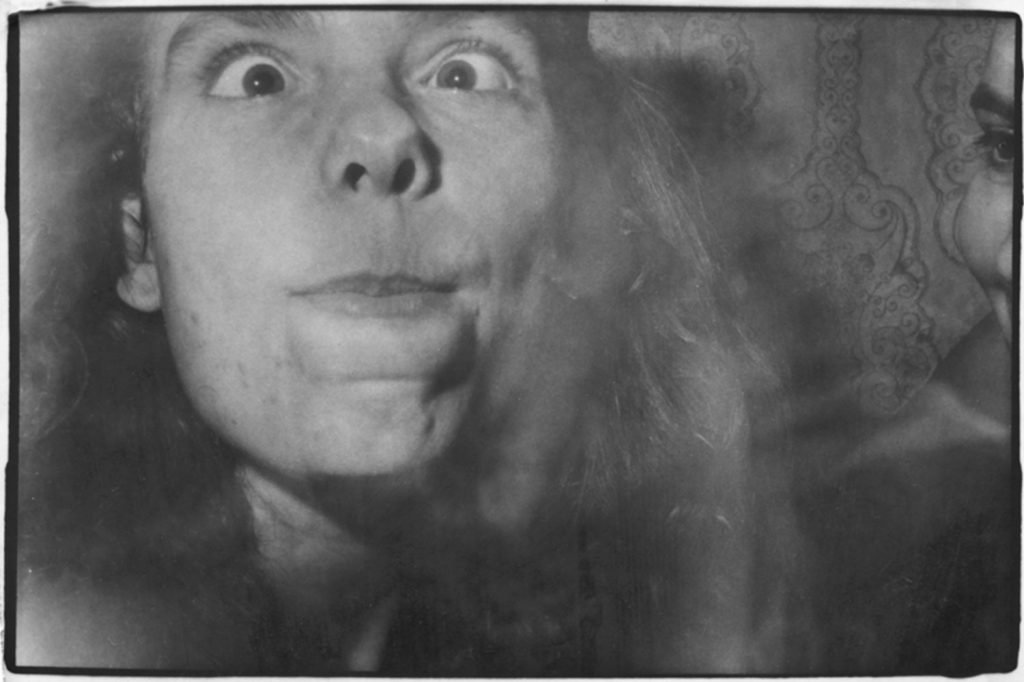

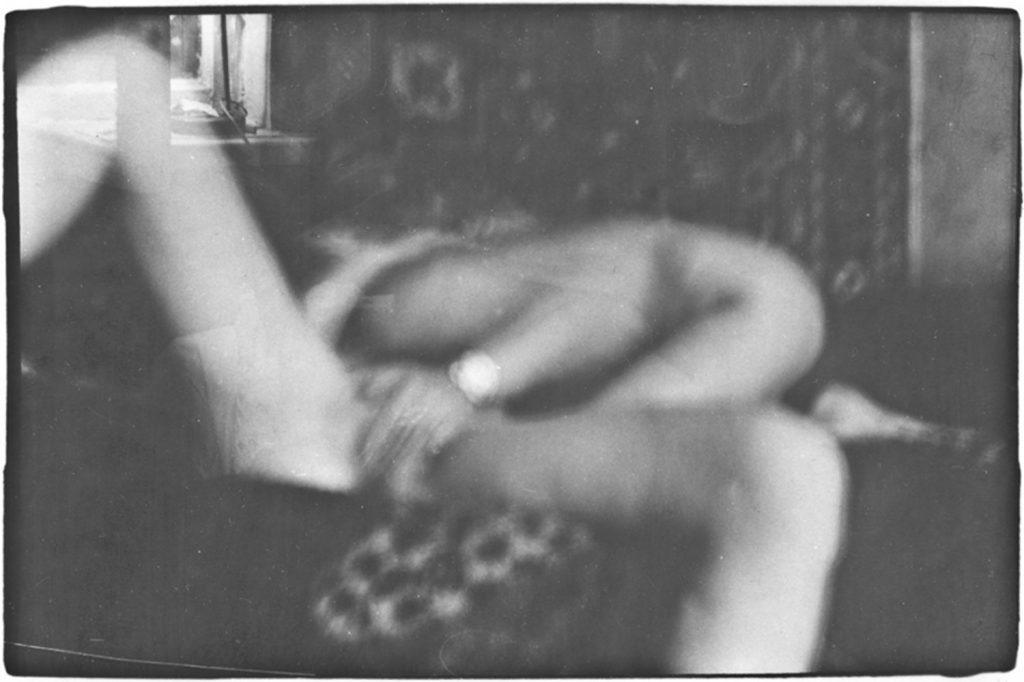

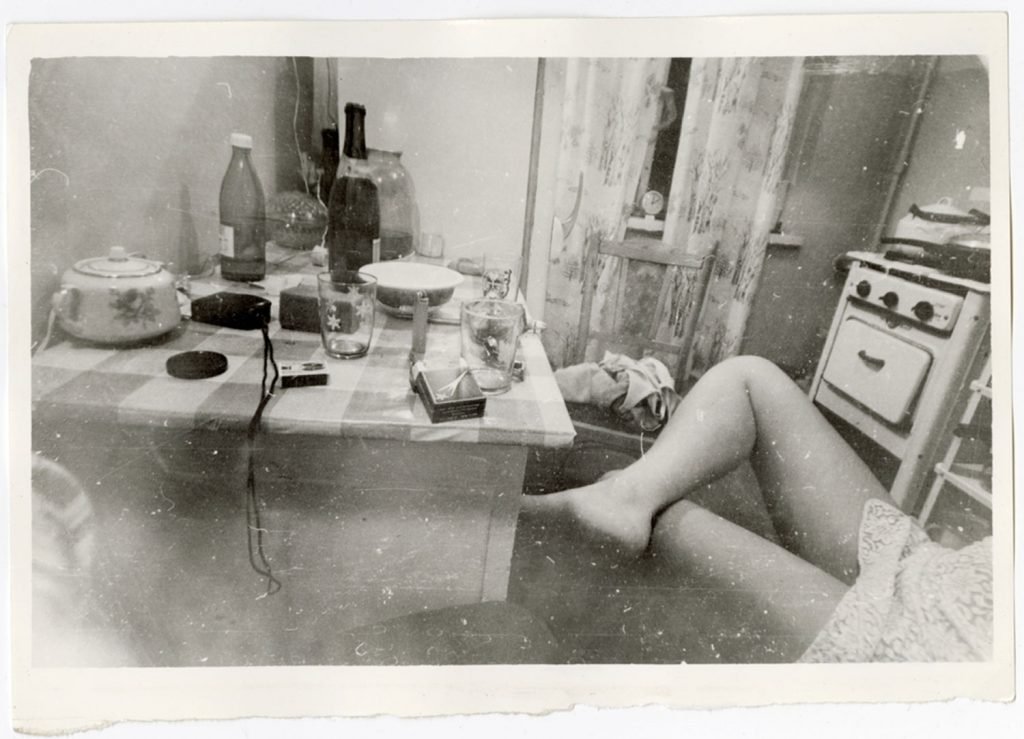

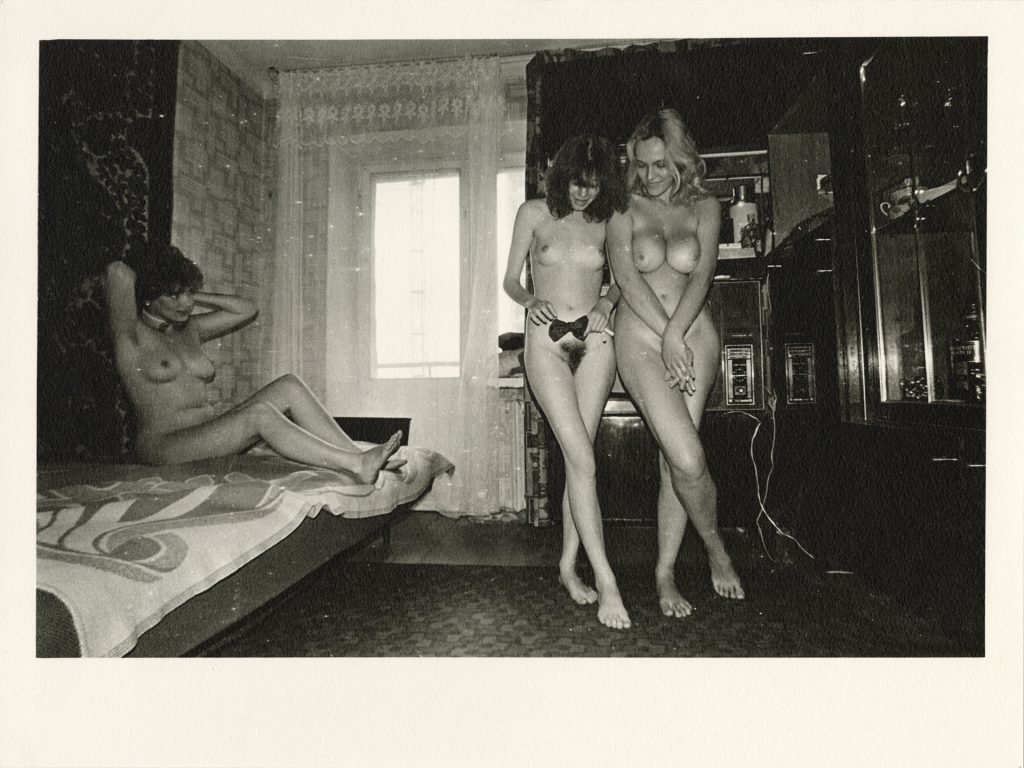

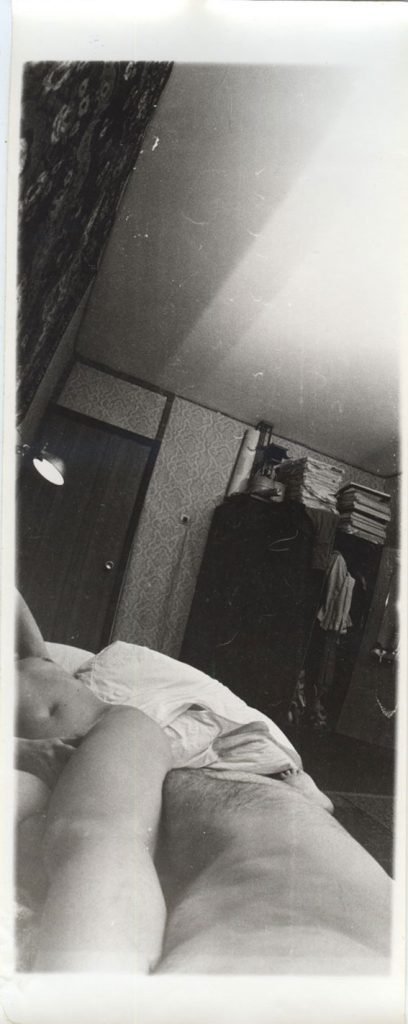

Still, a great number of his early works from the beginning and the middle of the 1980s weren’t intended as series, but acquired a form of “cinematographic” documentation of a sequence of events (although nothing is said in them about “events” as a certain outstanding moment in the development of the situation). At the same time, they already had certain topics outlined in them, which the author would work with in the following decades. One of those topics was that of private space. Boris Mikhailov was one of the first ones to address it at his time in his Private Series at the end of the 1960s. The series was partly made at home. In the 1980s Roman also took black-and-white nude photographs against the background of Soviet communal kitchens and the apartment the author had moved in with his first wife. The naked body that will later become the keynote of the photographer’s legacy here isn’t yet perceived as an exponent of a certain idea. It remains a body – sensual and full of life. The author refused idealisation and refinement of body shape, leaving all of his models’ “flaws” like cellulite lumps, little breasts and fat rolls as they are. The protagonists of his photographs were usually people from the author’s immediate circle (and sometimes the author himself). Thus, camera couldn’t perform the function of an unbiased observer, documenting personal relation to the people and the objects in the frame. This connection with personal space is expressed in how tactile each of the photos is: the author savours the gestures, touches, the details of the interiors and clothes (porcelain ware, carpets, wallpapers, lace stockings or slippers in the foreground of the photo).

The most intimate are vertical and horizontal scenes in the bathroom and in bed, taken with a panoramic camera in 1985. That format, framing and fragmented composition create “peeking” effect. The photographer’s refusal of privilege to stay “unseen”, as well as the presence of personal view is almost physically felt in each of Pyatkovka’s photographs, forming their prominently expressed masculine nature, which is typical of Kharkiv School of Photography in general. This regards not only and not so much masculinity as a gender characteristic, although Kharkiv photography scene was a male-dominated environment, but rather the way of perceiving the surrounding world. Masculinity, in this case, should be understood as an ambition to dominate or to have power over an object, whether it is the object in the frame or the photograph itself as a physical object [2]. From this point of view, the deep interest of Kharkiv photographers in manipulations with and deconstruction of a photographic image is non-accidental.

In Roman’s early works, certain “dullness” of reality was present: the models were expressly isolated from the outer reality and merged with their communal cocoon, seen as the only refuge free from the control of the system. The photographs weren’t representing the historical situation and didn’t appear as a result of its analysis, but were the immediate constituent of everyday life. As Elena Petrovskaya has aptly characterised that notion, “Everyday life means dulled sensation. There are no shocks or painful blows from the surrounding world, even if the latter still delivers them. Everyday life is absent-mindedness.” [3]. Intimate and quiet prints mentioned above didn’t have the provoking tone common for Roman’s series from the end of the 1980s. Even in the most explicit photographs the emphasized naïvety preserves the wholeness of the characters which doesn’t let the view “prepare” the images (a pornography method of replacing individual erotic sensuality of a person with an intensive flow of impulses, stimulating with their hyperrealism).

It is worth pointing out that along with direct photography, among the first photos, there are experimental collage works. The appearance of this technique in the creative arsenal of the artist was a sort of tribute to its popularity among the representatives of Kharkiv School of Photography. Still, collage didn’t become a tool that would answer the requirements of Pyatkovka’s creative view. For Roman himself, the starting point of his creative work was the series made in another “signature” technique for Kharkiv School of Photography, which is superimposition (overlapping of two slides). This regards Internal Anxiety (the beginning of the 1980s) and Sandwiches of Memory (1983). In both cases (especially in the first project) the influence of Mikhailov and Maliovany is noticeable. It is revealed in the colouristic choices in the images.

While Mikhailov and Maliovany used their own slides for the “sandwiches”, Pyatkovka worked with borrowed photos. In Sandwiches of Memory, the author used art reproductions and the FED factory archive as a base, combining them with the photos he took himself. Appropriation became an important method for the photographer, and he later uses it in Vegetable Store series (1990), where luriki are combined with close-ups of fruits and vegetables. Sometimes video became the source of the “pictures”: in Uniformity of Diversity series (1992) one of the panels was composed of porn film stills with the faces of orgasming women in them. Among later appropriation-based works that can be pointed out, there’s Sovetskoe Foto (2013), a nude series combined with pages of Sovetskoe Foto, the official publication of the USSR Union of Photographers, which most of the Soviet artists dreamt of being published in. Getting back to superimpositions from the beginning of the 1980s, let’s point out that being overloaded was their typical feature. The compositional density created at the intersection of various visual and informative flows gives it a surrealistic after-taste which can be considered as a conscious decision since the artist admits the interest that Salvador Dalí evoked in him and in his colleagues at that time.

The middle of the 1980s was marked with the emergence of new tendencies in Pyatkovka’s creative work. Thinking in separate “pictures” was finally replaced with gravitating to conceptual series in which more aggressive work with the topic of physicality came to the forefront. In the works of the older generation of Kharkiv School of Photography before the 1980s, nude photography didn’t cross the line of erotica in salon interpretation of this notion. In the collages by Rupin and Maliovany the nakedness used to be a “reason” for experiments with plastics. According to the words of Oleg Maliovany, “In fact, there wasn’t even erotica there. In our group’s photographs sensuality as a desire to possess a woman (the Vremia group – ed. note) was absent.” [4]. The works that can be called the exception from this formalist tendency are the works by Mikhailov, who brought the explicitness of his frames to anti-erotism, and Violin (1971) by Yevgeny Pavlov. The second generation (Pyatkovka, Solonskiy and Bratkov) developed a more radical interpretation of physicality. It became obvious in Roman’s Bitch Love series (1985) about homosexual love between two women and in Wrong Picture (1986) performed in superimposition technique and dedicated to the development of child sexuality and its formation in the conditions of a general taboo on this topic.

A notable change in the intonation of the photographer’s works coincided with the transformation of the art situation in the last years of the Soviet Union. That was, first of all, liberalization of life, even though that was a very gradual process, and distinct “thaw” in the sphere of the external policy. Foreign specialists that ever since the 1970s had been showing interest to what was happening behind the “Iron Curtain” now had more opportunities for communication and organization of exhibitions of the Soviet non-official art and publishing of their works in foreign journals [5] . As a matter of fact, Pyatkovka started being exhibited in Kharkiv and abroad almost at the same time. The first exhibition in his hometown was F-87, organized by Misha Pedan in the Palace of Students of Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute. And just in a year, in 1988 his works were shown in Galerie 4 in Prague at the Aktualita SSSR exhibition. In 1989, at the invitation of Polish curator Daniela Mrázková, Roman took part in the first foreign project, 150 Years of Photography, held in Prague. His New Hero series (1986), photos of punks with the lyrics of punk songs from that time, was included in the exposition of this project. At about the same time a photographer from Moscow, Igor Mukhin, created his photo series featuring members of nonconformist youth subculture. Still, Mukhin took a lot of photos at concerts, flat parties or in the streets, while Roman Pyatkovka limited himself to close private space. The existence of such a countercultural movement that refused any kind of ideology and authority of the ruling establishment in a totalitarian state undoubtedly intrigued the West. The photographer started actively exhibiting his works at foreign venues. Getting familiar with the international context and the new demands that it formed, encouraged the artist to distance himself from the surrounding local situation. His fusion with it was replaced with the view from the outside and self-reflection. It is revealing that in his works this distancing was veiled with the illusion of maximum intimacy with models and the ambition to remove all kinds of barriers and taboos.

One of the forms of self-reflection which naturally continued the appropriation method was systematic work with archives, both his own and other people’s. Using them let the author simultaneously knock together a number of semantic layers: personal, historic and artistic. In the first place in this context, it is important to mention Golodomor. Phantoms of the ‘30s (1988), created under the impression from a samizdat essay with the evidence of the genocide that had happened in 1932-1933. It was published by an elderly dissident living not far from the photographer. The series unites stylized portraits of the victims of the government-induced famine. The portraits were made from the frames used for luriki, but instead of colouring the film, the author scratched it and added details to the characters which gave the monochrome images other-worldliness and disturbing mood. Two of the works were staged and shot specially for the project. The artist considered this intrusion into the ‘authenticity’ of the archive totally legit since in that case photography served only as a semi-product which an artistic myth was crystalized from. Mythologization and juxtaposition of stories around Pyatkovka’s works are important for a deeper understanding of the material. That was why the author made up a unique story for every character of the series, which helped to de-anonymize them. Another aspect that contributed to it was that most of the pieces were made of group photos, and the artist deliberately leaves the details (for example, a part of a shoulder), that would remind the viewer of the presence of other people there. The factor that makes Phantoms stand separately from the general direction of the creative work of the author himself, as well as from that of his colleagues is appealing to the national topic. Basically Kharkiv School of Photography treats the problem of national identity with total indifference in the Soviet period. This detail is especially noticeable in the contrast with the rest of the Ukranian non-official art formations in Kyiv, Lviv and Zakarpattia.

The moving force of Phantoms is balancing between individuation which manifests personality in mass society and emphasis on typical traits. The same approach can be noticed in I Come from Childhood (1991): photos from a holiday trip to Simferopol in 1964 occasionally found in the family archive were used for a series of luriki-styled coloured “picture”’. In these photos there’s also that split between the unique (the heroes and the situation directly connected with the author) and the typical (posing in front of monuments – frames like that can be found in most of family photo archives). According to Pierre Bourdieu, vernacular photography turns into a social marker, so a person being photographed is posing in the surrounding that’s chosen, first of all, for its symbolic value (though it can by chance have aesthetic value as well) [6]. Pyatkovka took up that “I was here” cliché gesture and brought its kitsch nature to the maximum with the help of colouring which mimicked mass aesthetic preferences. A significant aspect for analysing the series is also the fact that it was closely connected with the pages of the author’s life itself since working with personal archive would later become a regular practice for him.

A similar principle of the use of colouring as a visualization strategy can also be seen in Holidays project (1986-1989), consisting of coloured direct shots from public events. Artificially intensified palette through irony reveals the rhythmics of the “collective body” and the absurdity of the environment in which it exists. However, without any doubt, it would be a mistake to link the colouring method solely to playing with the phenomenon of kitsch. Maternity Hospital series (1987) initially was intended as a documental one, but Pyatkovka felt that “clean” shots wouldn’t be able to show the fear and helplessness of the women that he saw in the maternity department at the time of the photoshoot. It was only adding colours that helped achieve the necessary level of tension. Again, intrusion into the field of the shot can be perceived as an allegory of violence – in this context both social and physical.

The role of various manipulations with photographic material was gradually enforced in Roman’s works at the end of the 1980s. That wasn’t complete dominance over the media, but rather a theatrical approach in which a director (photographer) does all the preliminary work for implementing the idea, but leaves a certain performative space for the models to improvise. In her essay Tatiana Pavlova highlights this peculiarity, saying that staged photography for the author was encouraging a person to play a role in front of the camera [7].

Adultery series (1988) was shot with a wide-angle lens with long exposure in a dim space, lightened with a flash. Due to that static objects remained sharp, while moving ones turned out blurred. That blur in combination with post-processing (hand-colouring among other things) expressively demonstrates the author’s narrative about a love triangle between “him, “her” and “a mistress”.

The diversity of techniques, typical of Kharkiv School of Photography, to a certain extent, compensates the eternal complex of photography in relation to other art forms because of its printed nature. The photos from Games of Libido series (1989-1995) were made in the technique that gave a single copy since the negatives were basically destroyed in the process of printing the photos. The traces of erosion on the material and the ruthless violation of its integrity are in tune with the BDSM motives present in the project, which cross another line. The orgasticity of the compositions is in absolute dissonance with the idea of “obedient bodies”, the formation of which, according to Daniela Vukas, was one of the goals of the Soviet communal project [8]. The realization of this project had totally opposite result that turned communal apartments into spaces in which, as Vukas cites her Russian colleague, Olga Bezzubova, “social relationships, body practices and behavioural models excluded from the normal order of everyday life” were possible.” [9] It was that deviation that Pyatkovka was interested in. Witches’ Sabbath series (1988) shot together with Boris Mikhailov, was built on deliberate non-normativity of the characters’ behaviour. This series consists of nude pictures in the interior of a typical Soviet apartment the standardization and soullessness of which is well-defined against the ecstatic freedom of physical self-expression of jumping, laughing and posing models. The continuation of this line, dedicated to the ban on sensuality in public space and the fact that sensuality was encapsulated in private sphere, was Communal Apartment series (1991) with its coloured and “clean” staged nude photos in ironic mundane everyday scenes.

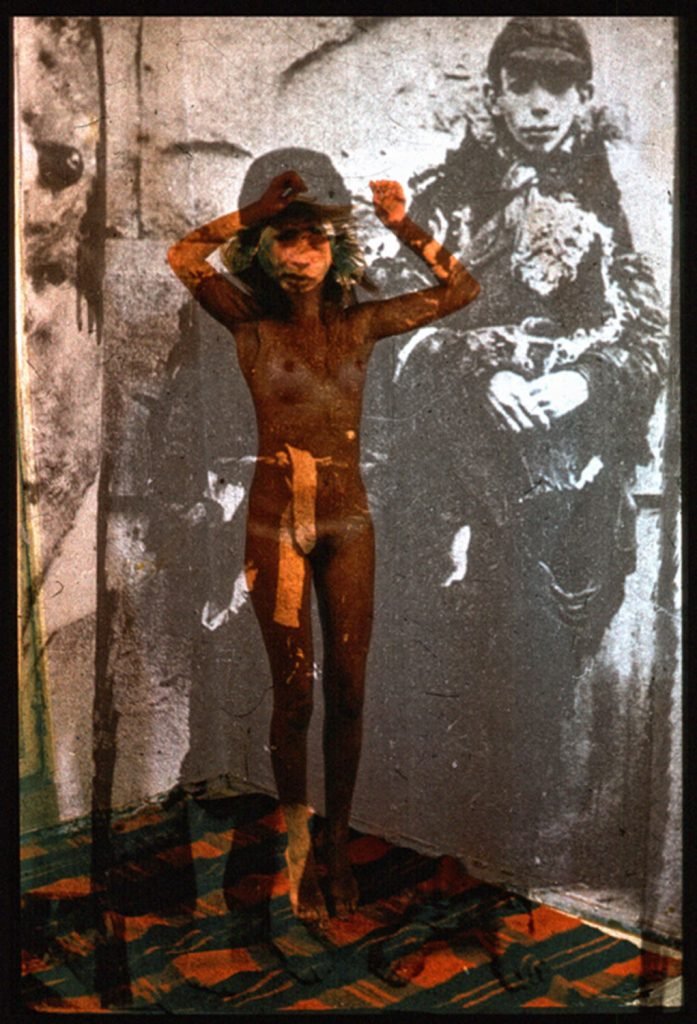

Some of the series, such as Games of the Naked (1988) or Sovetskoe Foto (2013) and Agitation Poster (2013) even more obviously unfold the conflict between the ideology-driven and controlled Soviet environment and the expression of sexuality. In all the three projects the author used the principle of superimposition. However, in the first case, the sandwich effect was achieved with the help of projection of the photos taken at a demonstration in Dzerzhinsky Square (now Freedom Square) in Kharkiv on naked bodies. Two other series were created in the technique of classic superimposition or technical combination of images. The photos had been taken by Roman and borrowed from the covers and pages of Sovetskoe Foto magazine or social posters.

Despite the fact that almost three decades have passed since the collapse of the USSR, dialogue with the Soviet past, according to the author, still remains inexhaustible and valid even today. Besides that, this topic becomes a base for consistent use of an established set of Kharkiv School of Photography’s aesthetic techniques, including conceptual instruments like the combination of a “picture” and a text. The idea of getting a hybrid wholeness via the synthesis of visual and textual narrative came to Kharkiv through Boris Mikhailov and a number of his series (Horizontal Pictures, Vertical Calendars, 1982, Viscosity, 1982, Unfinished Dissertation, 1984-1985). Pyatkovka adapts the format of photo-samizdat in You Wait book (1989), where explicit photos are combined with pages from a handbook for the pregnant. In order to understand the place of such a technique in the general Soviet context, it is important to remember an article “Conceptual Photography” by Valeriy Stigneev, which appeared on the pages of Sovetskoe Foto magazine the same year, in 1989. Written in naive, optimistic and sententious style, so typical of the articles published in that magazine, the article explains (also by the example of Boris Mikhailov) the principles of the interplay of image and text, which weren’t clear to an average viewer, raised on salon photography standards [10]. Right next to the article there is a negative review about it by Grigoriy Organov, who is speaking of the lameness of both conceptual photography as a notion and visual imagery, because, “in order to be called a photography artwork, a work must carry in itself, in its meaning and form, something artistic and inspiring.” [11]

That’s why even by the end of “perestroika” the Soviet photography scene hadn’t yet completely accepted the possibility and the rightfulness of conceptualist position. But in Kharkiv photography context it became one of the key pillars.

Pyatkovka continued to work with text as a significant component of his series in the 1990s and 2010s. However, the understanding of text in them is diverse, including even graphic elements. For example, in War Maps of Love (1993) and Schemes (1998), there are dotted lines, arrows and other signs drawn over photographs of a naked body. In Russian-English Phrasebook series (1997), as well as in Weather Forecast (2018) and There Is No Sex in the USSR! (2018) books the images are accompanied with clear text, either as a comment (like in Weather Forecast and There Is No Sex in the USSR!) or as a part of a composition (a list of cliché questions inscribed right on the models’ bodies in Russian-English Phrasebook). In the latter case, the communicative dynamics of the works look similar to superimposition: this combination of two absolutely autonomous messages brings forth the third semantic layer.

After working as a commercial photographer from the end of the 1990s until the end of the 2000s, Pyatkovka brought the elements of that experience into his further work. In his series from the end of the 2000s, one can hear the echo of glamour aesthetics (Dating Website, 2012, Dormitory Fashion Story, 2013) which is being synthesized with the methods mentioned above, such as appropriation, “sandwiches” and so on. Making a substantial contribution as a teacher into supporting photography in his home town and in Ukraine in general, the author has been involved in creative activity for more than four decades already. All that time his approach remains pretty homogeneous from both narrative and formal points of view, which makes it possible to mention his series from different years in the same line. Roman Pyatkovka follows the fundamental principles of Kharkiv School of Photography, such as working with mundanity and using a wide range of manipulations with photographs, and consistently explores the topic of intimacy as a complex synthesis of private and public.

KHARKIV PHOTO FORUM is the first interdisciplinary forum dedicated to a thorough analysis and contextual study of the Kharkiv School of Photography. The forum will be held on Аugust 18-21, 2020 in an online format. The main events of the forum will be an international scientific conference, exhibition projects, and talks with Ukrainian and foreign experts.

Bibliography:

- Тупицын, Виктор. Коммунальный (пост)модернизм [Communal (post)modernism]. Moscow: Ad Marginem, 1998, 9.

- Susan Sontag argues photography is a manifestation of the position of power in generalї: “Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood. To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge — and, therefore, like power” ( Sontag, Susan. “In Plato’s Cave”. On Photography. London: Penguin Books, 2008, 4).

- “Повседневность — это притупленность восприятия. Никаких шоков, никаких болевых ударов среды. Даже если последняя по-прежнему их наносит. Повседневность — это рассеянность” (Петровская, Елена. “На злобу будней” [Against routine]. Художественный журнал, no. 17 (1997). http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/52/article/1039).

- Сандуляк, Алина. “Харьковская школа фотографии: Олег Малеваный” [Kharkiv School of Photography: Oleg Malevaniy]. ArtUkraine, 2016. http://artukraine.com.ua/a/kharkovskaya-shkola-fotografii–oleg-malyovanyy/#.XS4Z4HtS94E.

- We are taling about Another Russia by Daniela Mrazkova (1989), “Up from Underground, Aperture issue, dedicated to Soviet “perestroika” (“Photostroika: New Soviet Photography”, 1989), Toisinnakijat/Seeing Different by Taneli Escola and Hannu Eerikainen (1988)

- “… becomes a sort of ideogram or allegory, as individual and circumstantial traits take second place. The person photographed is placed in a setting which is primarily chosen for its high symbolic yield (although it can also and incidentally have an intrinsic aesthetic value) and which is treated as a sign” (Bourdieu, Pierre. Photography: A Middle-brow Art. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996, 36).

- Pavlova, Tatiana. “Avanguard red and green. From ‘Blow theory’ to ‘Kontact’ ”. VASA Journal on Images and Culture. http://www.vasa-project.com/gallery/ukraine-2/tatiana-2-essay.php/.

- Вукас, Даниела Лугарич. “Коммунальная квартира как гетеротопия”. [Communal appartment as heterotopia] Гетеротопии: миры, границы, повествование: сборник научных статей. Vilnius: Vilnius University Press, 2015 198-210.

- Ibid., 205.

- About Boris Mikhailov’s “Самотність”: “Автор не случайно выбрал именно такие снимки. С искренностью и наивной простотой, свойственной “семейной фотографии”, они повествуют о людях, о старой как мир теме любви и одиночества” [That wasn’t an accident that the author selected the very those shots. With sincerity and naive simplicity, typical of “family photohraphy”, they tell about people, about the world-old topic of love and solitude] (Стигнеев, Валерий. “Концептуальная фотография” [Conceptual Photography]. Советское фото, no. 9 (1989), 30).

- “… чтобы быть признанным произведением фотографического искусства, любое такое произведение должно нести в себе, в своем содержании и форме, в самом духе нечто артистическое, вдохновляюще художественное” (Органов, Григорий. “ “Концептуальная фотография?”: повод к поискам повода для размышлений” [“Conceptual photography?”: An Occasion for Reflection]. Советское фото, no. 9 (1989), 33).