Giangiacomo Cirla: I want to start with a question about your relation with objects, the heart of your work and subjects those categorize your projects. Where those your analysis starts?

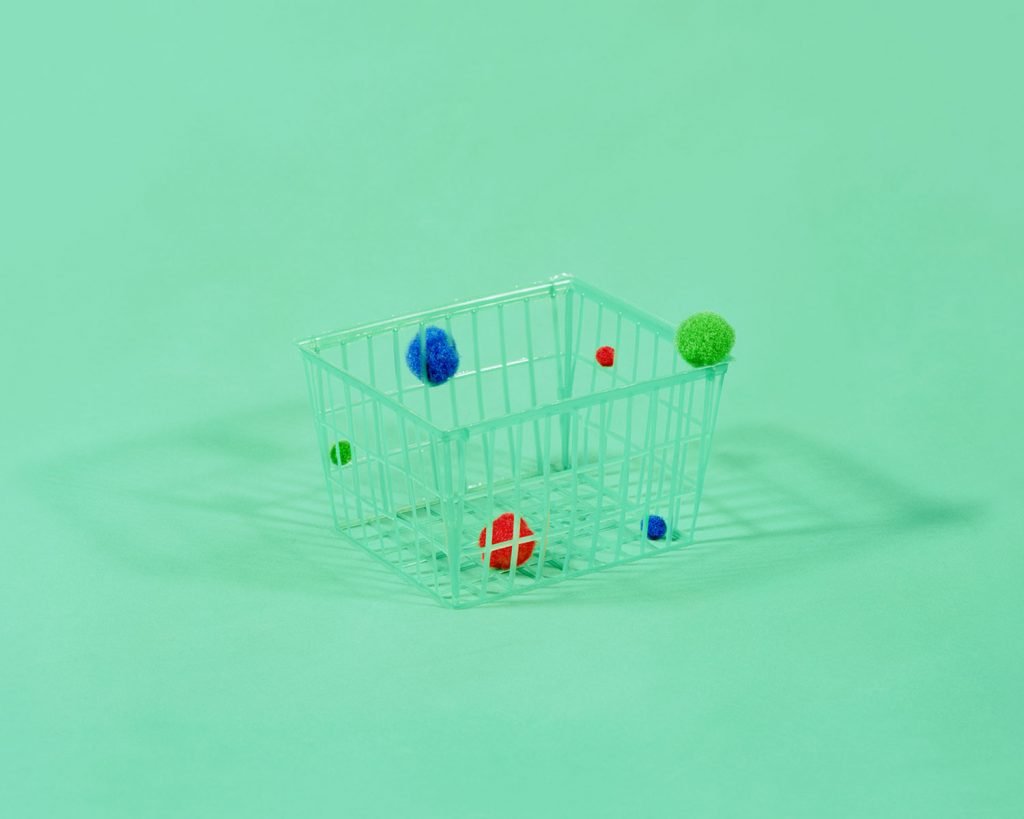

Mauricio Alejo: I think I relate with events more than with things. In that sense, it is not the object that calls my attention but certain disposition a specific object has in the world.

Now, on a different level, there might be a deep psychological reason for my inclination toward the inanimate world. For example, as an artist, I’m barely interested in portraits not because I don’t find them appealing but because a face is overwhelmingly expressive and I find very hard to tame that intensity for newer purposes. Objects, on the other hand, are quiet, subtle and docile.

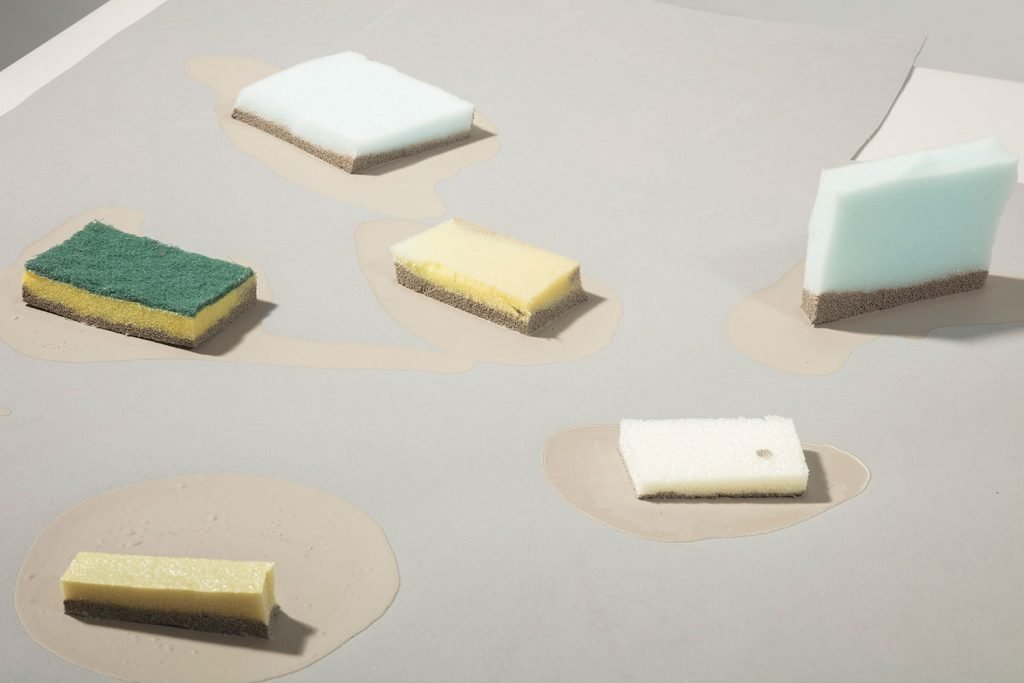

GC: Objects with a new narrative that does not obey their functionality. Is this the result of a long study on the subject or we are talking about impulsivity?

MA: It’s the result of both. I studied art, so for better or for worst, there’s always that little voice at the back of my head asking “from what you do, what is relevant to the big scheme of things?”. At the same time, there’s also this other part that is irreverent and deals with the gratifying experience of amusement and playfulness. In other words, I think one part sets the path and the other enjoys the landscape.

GC: I think that exist a strange power game between the new narrative that you give to the objects and the narrative result of the adaptation to the exhibit needs; an additional functionality attributed to them retrospectively when they became “art-objects”…

MA: I think you are stretching the word “functionality” a bit too much to make room for two completely different kinds of objects but you’re right that any given art piece suffers a meaningful transformation when it gets subjected to a curatorial process. It’s not the same when the piece is all by itself than when it is surrounded by other art objects in an exhibition space. Art objects are, so to speak, “symbolic devices” and context greatly influence their possible meanings. But if art is able to create new, unexpected meaning, it is precisely because it doesn’t serve a function like a chair does. If for the sake of argument we assign the word “function” to whatever an art-work does in a gallery we also have to acknowledge that this “function’ is really dispersed. There’s a great level of ambiguity in any art-work and the meaning or experience it conveys is incredibly malleable even when presented in a highly conventionalized fashion like a framed photograph. An exhibition might disregard a specific experience this object puts forth but might be successful at amplifying other experiences or concepts by analogy, repetition or contrast or by simple sequencing. In any case, I don’t think assigning new meanings to an existing piece is a compromise but a possibility already inscribed in the art-object itself.

GC: In this regard, we recently saw your work exhibited in ZsONA MACO Foto 2018 presented by CURRO. What is your relationship with this fair and in general with the exhibition system?

MA: I’m glad you brought up this question. I have to say I’m not estranged to the art market. I’ve been represented by galleries almost since the beginning of my career but I’m also an artist that has exhibited extensively in non-profit spaces and whose work is in public collections.

The relationship between art making, criticism and selling is not black and white and is not in any way as straightforward as people like to think. Sometimes there’s tension, sometimes they are complementary, some other times there’s antagonism. They could be mutually exploitative yet productive in the symbolic level. I find fascinating that the art scene is able to host artists that have no respect for art institutions yet they are able to express it within the institution. I don’t see a contradiction there and I don’t think their criticism gets neutralized in this context mainly because questioning, criticism, and dismantling lays in the nature of contemporary art itself.

In the context of the images you are showing here, the objects I photograph belong to a pool of objects that their main trait is their availability. There’s nothing heroic about them and I think of them as stand-ins more than anything else. They obey to an exhaustion of objecthood in contemporary image culture but I like to bring in the paradox of creating other objects out of them that will get circulated within the art institutions and by art institutions, I mean exhibiting spaces or this very publication you invited me or the art market.

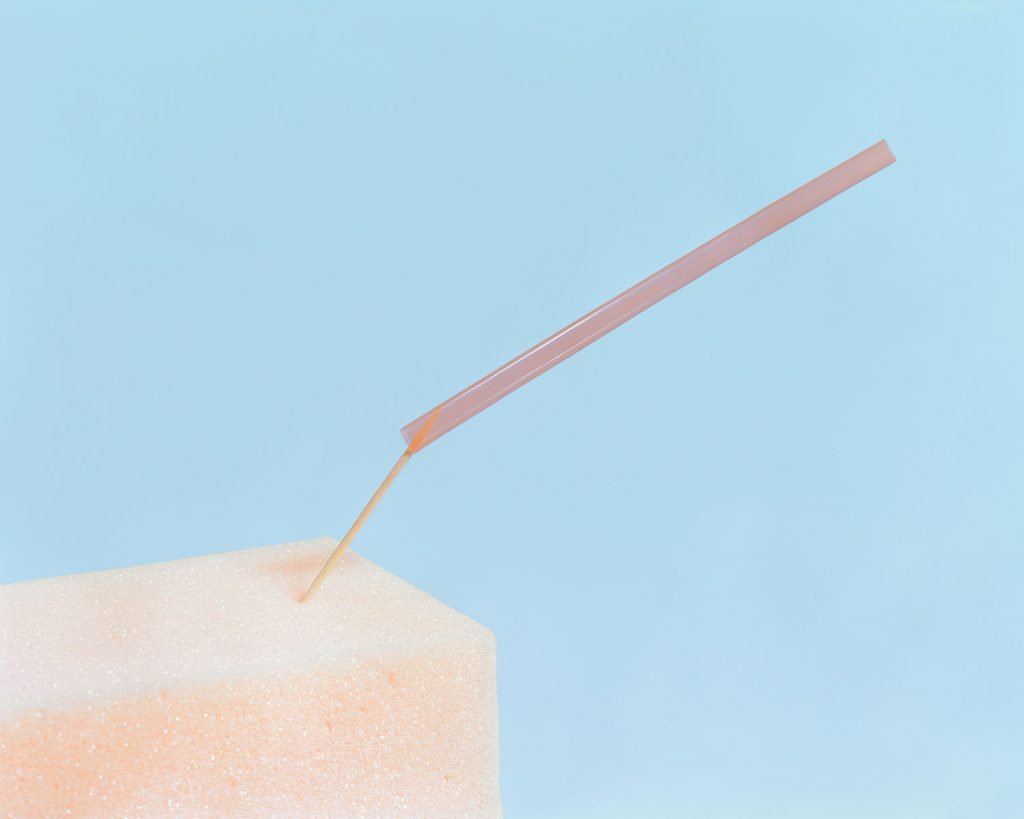

GC: Your works seem to be structured around a fine balance, what we see always seems to be in the point of giving up. This condition of suspension creates something else around things…

MA: I think that “something” is the physical evidence transformed into psychological experience. For example, some of the images you mention might produce a feeling of vulnerability but I think we could agree that this is not in the image itself but in the way you experience it. Furthermore, I think experiences don’t equate to verbal counterparts. We can use tension and precariousness to describe these images but knowing the concept is different from actually having the experience. I enjoy when I’m able to make it happen and that’s how my work relates to sculpture.

GC: You also work with other different media, like video and Installations; why this need and how it relates to your photographic work?

MA: Like I mentioned in a previous answer, my work has a strong relationship with sculpture and in that sense, my photography is the outlet of a broader interest that also takes video and installation as a medium.

GC: Your video projects make your method clear, out of time and space, attention goes to details, to the little things those compose the image. Another interesting meaning of your work is embodied in your objects’ vulnerability, the certainty that everything in life is hopelessly bound to collapse…

MA: Oh! don’t get me started on that. At the core, I’m a nihilist. A lot of my photographs portray that happy moment where things seem to be in balance and the illusion gets perpetuated by means of photographic stillness. I don’t want to make you sad or anything but the tension within comes from the fact that collapse is bound to happen. As human beings, we are constantly fighting chaos and gravity. We don’t go with the flow, we pride ourselves on building things and keep them up straight but in the universal time, entropy is going to win. There’s no way we are going to defeat the 2nd law of thermodynamics and chaos will be the only thing in our universe.

GC: Studies and works have taken you to many parts of the world but you now live and work in Mexico City, your birthplace. What relationship do you have with your homeland?

MA: I lived in New York for 13 years. Have you heard New York is an expensive city? Well, it’s true. At one point it just became practical to work in Mexico. Here I can do more with less.

GC: What’s the contemporary artistic situation in Mexico and how does the photography fit in?

MA: During the time I was working and living in NY, the situation in Mexico regarding violence really deteriorated. Like any art scene should do, a lot of artists focused on this subject matter which was urgent to address. There was already a conceptual trend in Mexico but it got explicitly political and social. We all know that photography, for the nature of the medium is always asked to bear witness when big transformations or social trauma happens. When I came back my work was mainly concerned with my immediate surroundings and the exploration of the medium itself, so there was not much room for me at that moment; but I didn’t take issue with this. I was aware that there were more pressing issues to attend. I didn’t change my work to accommodate this new reality either. I kept honest with myself about what I wanted to address as an artist. In the meantime, I kept showing and exhibiting internationally and despite the fact I wasn’t showing much in Mexico, my peers were interested about what I was doing and I was invited to give talks and lectures about my work. Recently I’ve seen the rise of a younger generation to whom I feel more connected to. I wonder what do they think about my work.

GC: Are there external influences, outside the mainly artistics, that affecting your work?

MA: I’m an atheist with two big concerns, one is the origin of everything and the other is consciousness. I read about neuroscience and physics to ease my existential anxiety. I suspect this, somehow influences my work but it does it in ways I’m unable to see.

Mauricio Alejo was born in Mexico City in 1969. He earned his Master of Art from New York University in 2002, as a Fulbright Grant recipient. In 2007, he was a resident artist at NUS Centre for the Arts in Singapore. He has received multiple awards and grants, including the New York Foundation for the Arts grant in 2008. His work is part of important collections such as Daros Latinoamérica Collection in Zürich. His work has been reviewed in important journals, such as Flash Art; Art News and Art in America. He has had solo exhibitions in New York, Japan, Madrid, Paris, and Mexico. His work has been shown at CCA Wattis Institute of Contemporary Arts in San Francisco; Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid and The 8th Havana Biennial among other venues. He currently lives and works in New York City.