TO WHAT EXTENT PHOTOGRAPHING NAKED PEOPLE POSES ISSUES AROUND ETHICS AND OBJECTIFICATION IN BORIS MIKHAILOV’S CASE HISTORY?

Text by: Antonino Barbaro

Introduction

When the book Case History by Boris Mikhailov first came out, it was met with the rare response of shock and outcry. Many people felt offended by its content and attempted to publicly shame Mikhailov (von der Heiden, 2003).

The book, a five hundred pages heavy volume, depicts the homeless people of Kharkov, Ukraine from the early to late 1990s. The time period when the Soviet Union had just collapsed and the transition from Communism to Capitalism was taking place throughout the ex-Union.

After having completed his scholarship in Berlin, Mikhailov decides to return to his hometown and set about documenting its historical transition, a testimony of the aftereffects of the Communist experiment.

Once arriving in Kharkov, Mikhailov was immediately met with an unexpected reality. Planning to focus his project on the new flourishing shops and businesses appearing all over the city, with their diverse range of foreign products and signs; attracted further by his fellow citizens’ change of attitude, all influenced by a new capitalist way of living.

Next to the new shops and shining business buildings, the other face of Kharkov was devastated by the never-before-so-high number of homeless people living on the street in barely human conditions. Kids were as rotten as older people and life expectation of both ones was terribly short.

Mikhailov decided to rethink his project and forget about the flourishing new Kharkov, focusing instead on the new homeless community, crushed by the economic shift and forgotten by their own people.

The photographer felt that traditional means and technics of documentation would have not been able to express the subject in a way that would make justice to it, or at least as he wanted the subject to be viewed and received by its audience (Kinsella, 2011).

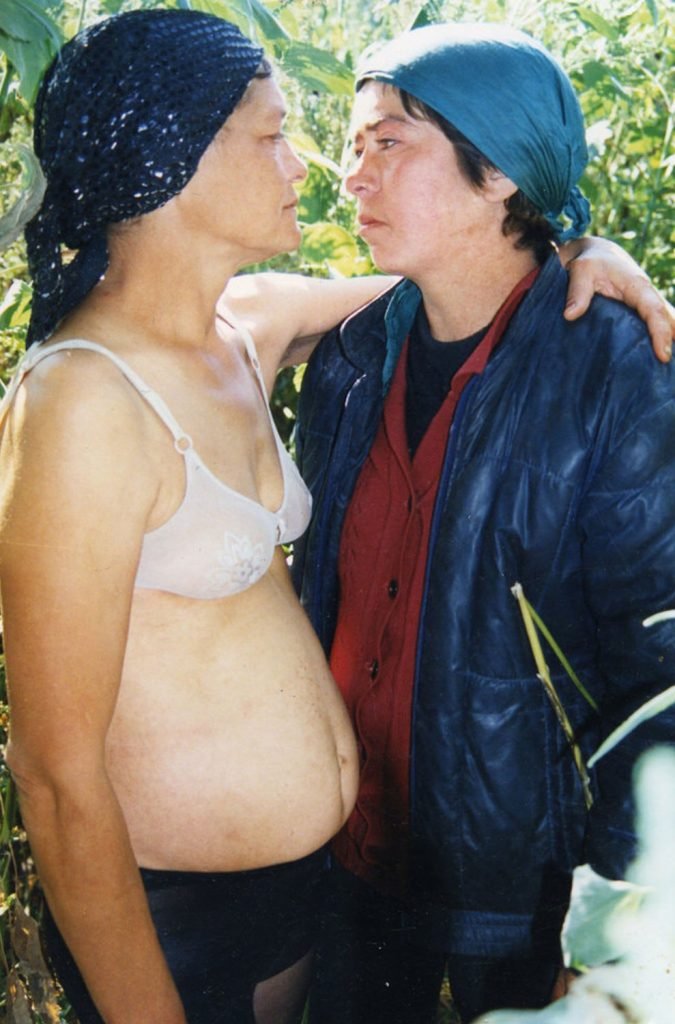

To better depict the landscape of poverty and desolation he was facing – but also according to his photographic style he had developed through years of projects around social matters similarly related to the Soviet influence on his society – Mikhailov had opted for a representation of the homeless people that focused on posing their naked bodies for the camera and viewer’s eye. By doing so, Mikhailov directly highlights the suffering and pain invisible to its fellow citizens and the rest of the world (Mikhailov, 1999).

This essay will analyse to what extent the choice of unclothing the homeless and asking them to pose naked for the camera can be considered ethical and does not objectify its subjects. Moreover, it will consider to what extent Case History had served its purpose and if it might have fallen into the mere sphere of sensationalism. Finally, it will question how appropriate and sympathetic this type of approach was for the people involved.

Discussion on naked body

The naked body has always had his specific place and name in the History of Art: the nude.

According to Clark, the nude “is an art form invented by the Greeks in the 5th century B.C., just as the opera is an art form invented in 17th-century Italy (Clark, 1957).

Clark mentions in his writings that there is a big difference between the nude and the naked body.

“To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes and the word implies some of the embarrassment which most of us feel in that condition”(ibid.), whereas the nude is a body that has been re-formed, deprived of its imperfections to aim at the ideal (ibid.) In this case, the differences between the two are quite evident and this could make us think that a representation of a naked body that is natural and doesn’t aim to an ideal it is not a nude.

The problem is more complicated than Clark’s effective, but rather simplistic dichotomy. As Nead argues, this solution “depends upon the theoretical possibility if not the actuality, of a physical body that is outside of representation and is then given representation, for better or for worse, through art; but even at the most basic levels the body is always produced through representation” (Nead, 1992).

The representation of a naked body will always be a representation, and therefore a nude, whatever its aim is the ideal or the reality of its state.

It is agreed with Clark that the History of the nude had, till his time, mainly been made of re-formed, ideal bodies that aimed to an almost supernatural beauty; but what he seems to be missing is that the nude and its representation in art has evolved and will always do. Even though the new nudes appear to be very different to the tradition and nobody seems to call them like this anymore (Borzello, 2012). “In its refusal to edit out the unacceptable, the new nude represents something not seen before in art. It is a very naked nude, created to confront today’s attitudes and anxieties” (ibid.).

If we look throughout Mikhailov’s vast body of work, we clearly see how the nude always had a significant space and function (Stahel, 2003).

Since the very beginning, Mikhailov’s interest in the nude had serious repercussion to his life and work, such as the loss of his engineering job and his respectability (Mikhailov, 2000), but also allowed him to manifest his dissent toward the official art promoted by the regime (Mikhailov, 2006).

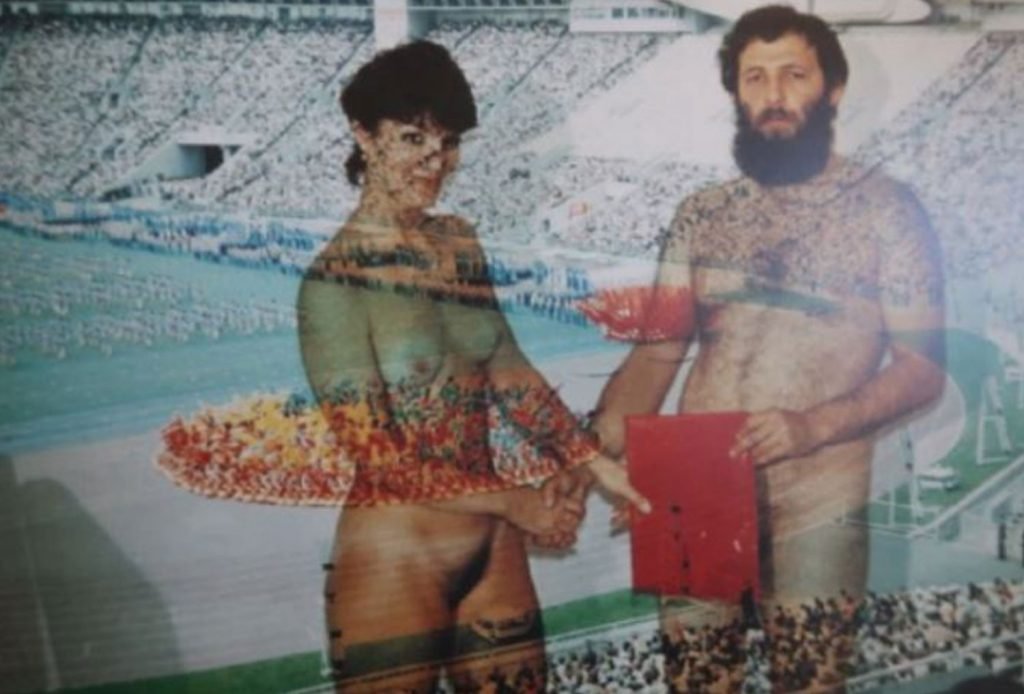

His first nude pictures, paradoxical consequence of the soviet laws on the matter (Degot, 2003), where the ones of his wife Vita, friends as well as occasional models. Most often in intimate settings, these pictures had a visible erotic tint, even when openly funny, linking them to the tradition of re-formed, ideal bodies previously mentioned and in accordance to Clark’s parameters of a good nude (Clark, 1957). However, the use of the images within his work was quite original and a break with the tradition. For one thing, the superimpositions of two different images in Yesterday’s Sandwich were concealing many coded allusions of forbidden subjects (Mikhailov, 2006).

In Case History, on the other hand, the use of nude is far more complex and multilayered. This nude is closer to the new “naked nude” of our age and therefore richer of neurosis representing the troubled society we live in. It’s a nude that quiet brutally shows real people suffering and in pain, that point fingers and asks for empathy.

What is captured in this book is the “misery of the social body and its decay in the 1990s, the agony of individuals, but also the millions of famine victims in the Ukraine of the 1930s, as they were never photographed and are now slowly being forgotten” (Stahel, 2003).

In order to give a voice to this agony of the individuals, one must let the pain speak. However, “physical pain has no voice” (Scarry, 1985), it resists to language – even more so, it “actively destroys it” (ibid.). In order to tell a story, physical pain has to find a voice outside of itself, of the individual in pain, therefore “it is not surprising that the language for pain should sometimes be brought into being by those who are not themselves in pain but who speak on behalf of those who are” (ibid.). Mikhailov in this circumstance, by photographing the naked bodies of the homeless, finds the voice needed to tell their story.

It does so by showing those bodies undressed, by exposing their pain to the viewer through the scars, wounds and infections. As mentioned by Scarry: “The point here is not just that pain can be apprehended in the image of the weapon (or wounds) but that it almost cannot be apprehended without it” (ibid.).

Case History and the ethical issue

After publishing the book, the accusations of immorality and unethical behaviour toward the author were many, and not so easily dealt with (Schube, 2003). Mikhailov had been accused of voyeurism, “offence against human dignity” (von der Heiden, 2003) and exploitation of the poor for own fame.

In addition, it has been said that “showing something like this under the pretence of “art” should not be allowed” (ibid.). Case History had the overall effect of shocking audiences and raising ethical concerns around Mikhailov’s work.

His images were so full of what Barthes theorised as “punctum” – that “something” of a photograph that catches, punctures our attention like no other image before (Barthes, 1980) – never failing to upset and ultimately provoke a strong reaction.

Among those accusations, the author had been criticised for paying his subjects, often offered them meals and drinks in exchange of their naked performance (Kinsella, 2011). Or as Schube described: “as a reward for displaying their misery”(Schube, 2003).

This monetary exchange is questionable, denoting to the fact Mikhailov is not only taking advantage of the participant’s unfortunate situation, but also objectifying as if they were exchanging a service on a marketplace. However, Mikhailov explains that the need for the nakedness of his participants requires us to explore other meanings behind this monetary exchange.

According to the author “Manipulating with money is somehow a new way of legal relations in all areas of the former USSR. And by this book I wanted to transmit the feeling that in that place and now people can be openly manipulated. […] I wanted to copy or perform the same relation which exists in society between a model and myself” (Mikhailov, 1999). The author treats his subjects, despite their condition, in the same way he would treat a professional model, and therefore materialises with this work the current social and economical situation him and his subjects were living in. In reference to objectification, Mikhailov would support that it is not as far from the many transactions we are used to; and by opposite results, it ends up elevating their status of forgotten-and-rejected from society back to the same one of other professional within society (Mikhailov, 1999).

In addition to that, the author mentions his duty as a documentarian to make a record of the social injustice of its time because “In the Ukraine there is no historical material about the past, and it is my duty to preserve for future generations material about the relationship between society and the homeless. As to the morality of paying these people for posing: it would be immoral not to pay them” (Mikhailov, 2000).

Moreover, in regards of the nakedness of those people Mikhailov “was interested in what would happen to a face when a body gets undressed. […] sometimes they, simply as people of the “new” morality, exposed their “values”. When naked, they stood like people” (Mikhailov, 1999). The performance he needed from them to create this work had to be considered as such and therefore adequately compensated.

At this point, and after giving some validation to the reasons and justifications at the way he carried his practice, we are left to ask ourself if maybe the whole idea of photographing the naked homeless – the others – fully displaying their suffering and wounds, for the eyes and delights of an audience who would be approaching this work comfortably seating in their living rooms, or through a pristine gallery wall; is it still an ethical work that we are looking at?

According to Rosler “documentary, as we know it, carries (old) information about a group of powerless people to another group addressed as socially powerful” (Rosler, 1981). In this specific case, the powerless homeless people of Kharkov are brought to visibility to the socially powerful audience of Mikhailov’s work. This explicits the power imbalance between the two parts and between the photographer and his subject.

If those images are meant to carry a substantial argument about specific social relations, they can work (ibid.), and therefore, their purpose is ethically fulfilled. Nonetheless, Rosler’s concerns address the fact that most of the times the documentary practice that has so far been granted legitimacy “has no such argument to make” (ibid.), ending up falling into generalisations and most often sensationalism. Ultimately, failing to generate positive change.

I would conclude that, even though the intentions behind this work were not to generate positive change (besides the immediate one supposedly experienced by the subjects), but to create a testimony of a specific time of great political and humanitarian importance, the work still carries the ethical merit of recording what would have otherwise been completely ignored by the generations to come. Testimonies of past atrocities are important in building a more civilised future for the human society.

As a citizen of his city, Mikhailov’s interaction with the subjects – and in some cases the development of friendships – is a far more positive attitude than the one of ignorance perpetuated by his fellow citizens.

Conclusion

As Nead states: “There can be no naked ‘other’ to the nude, for the body is always already in representation” (Nead, 1992). As a consequence of that, the naked bodies shown in Case History still belong to the realm of what in art is called nude.

However, it seems that the reasons behind this peculiar choice of representing the homeless of Kharkov has more to do with the aim of recording and providing a platform of expression for their pain and their identities, rather then exploiting their misery, or worst mere sensationalism and provocation. He has done so in the way he felt was the most direct and truthful to the situation (Mikhailov, 1999).

After examining the ethical question that this work arises, I believe that, although it did objectify – at least to a certain level – its subjects by engaging with them in a relationship scheme of exchange, such as model/artist or performance/compensatio, this had been done for the specific purpose of bringing to visibility a condition that would have otherwise gone unnoticed, and at its worst forgotten: their pain.

“In order to express pain one must both objectify its felt-characteristics and hold steadily visible the referent for those characteristics” (Scarry, 1985). Faces and wounds are here visible and recorded into images that we, as an audience, will have to confront to avoid that situations like this will happen again in future circumstances.

There has been no record of any mistreatment perpetuated on Mikhailov’s subjects, whether from the side of the author or from any indirect consequences that this publication might have generated once brought to public attention. Even if the participants did not have any positive outcome other than the money, food and company provided by Mikhailov, accountable only for the short term; it must not be forgotten how valuable this work will be for the future, for their memory and for the next generations of Ukraine and the world at large.

References:

- Barthes, R. (1980). Camera Lucida. 1st ed. London: Vintage, pp.25-28.

- Borzello, F. (2012). The naked nude. 1st ed. London: Thames & Hudson, pp.6-10, 15-20.

- Clark, K. (1957). The nude. 2nd ed. London: John Murray, pp.1-6.

- Degot, E. (2003). Unfinished Dissertation: Phenomenology os Socialism. In: U. Stahel, ed., Boris Mikhailov: a retrospective, 1st ed. Winterthur: Fotomuseum Winterthur, pp.102-104.

- Kinsella, K. (2020). The People Who Got into Trouble: Boris Mikhailov’s Case History at MOMA by Kevin Kinsella – BOMB Magazine. [online] Bombmagazine.org. Available at: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/the-people-who-got-into-trouble-boris-mikhailov-s-case-history-

at-moma/ [Accessed 7 Jan. 2020]. - Mikhailov, B., Knape, G., Groys, B. and Kaila, J. (2000). The Hasselblad award 2000. Göteborg,

Sweden: Hasselblad Center, pp.1-20. - Mikhailov, B. (1999). Case History. 1st ed. Berlin: Scalo, pp.5-9.

- Mikhailov, B. (2006). Yesterday’s sandwich. 1st ed. London: Phaidon.

- Nead, L. (1992). The Female Nude. 1st ed. London: Routledge, pp.2-16.

- Rosler, M. (1981). 3 works. 1st ed. Halifax, N.S.: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and

Design, pp.1-12. - Scarry, E. (1985). The body in pain. 1st ed. New York: Oxf. U.P. (N.Y), pp.3-161.

- Schube, I. (2003). Making Images: The Theatre of Bodies in Boris Mikhailov’s Works. In: U. Stahel, ed., Boris Mikhailov: a retrospective, 1st ed. Winterthur: Fotomuseum Winterthur, pp.154-157.

- Stahel, U. (2003). Private Pleasure, Burdensome Boredom, Public Decay – an Introduction. In: U. Stahel, ed., Boris Mikhailov: a retrospective, 1st ed. Winterthur: Fotomuseum Winterthur, pp.12-16.

- von der Heiden, A. (2003). Consumatum Est? Case History by Boris Mikhailov. In: U. Stahel, ed., Boris Mikhailov: a retrospective, 1st ed. Winterthur: Fotomuseum Winterthur, pp.170-171.