Giangiacomo Cirla: Hello Alexandra, we have crossed our path last time during UNSEEN 2017 when you were a finalist for the ING Unseen Talent Award 2017, what happened after that experience?

Alexandra Lethbridge: Lovely to speak to you again! Since then, I’ve been working on building that series, alongside working on another project ‘Other Ways of Knowing’. I’ve also been exhibiting work, most recently in New York and Copenhagen.

GC: On that occasion you showed your “The Path Of An Honest Man” series, an investigation of the hidden language of lying and its visual code. Can you tell me more about this work?

AL: When I started on this series I was working off the theme from the award, which was Common Ground. After my initial research, I decided on the idea of communication and language and how that could unite or divide people.

I started by thinking about methods of communication with a particular interest in non-verbal communication and unspoken languages and the ways in which we understand or misunderstand each other. I became particularly interested in body language, which eventually leads me to the subject of lying.

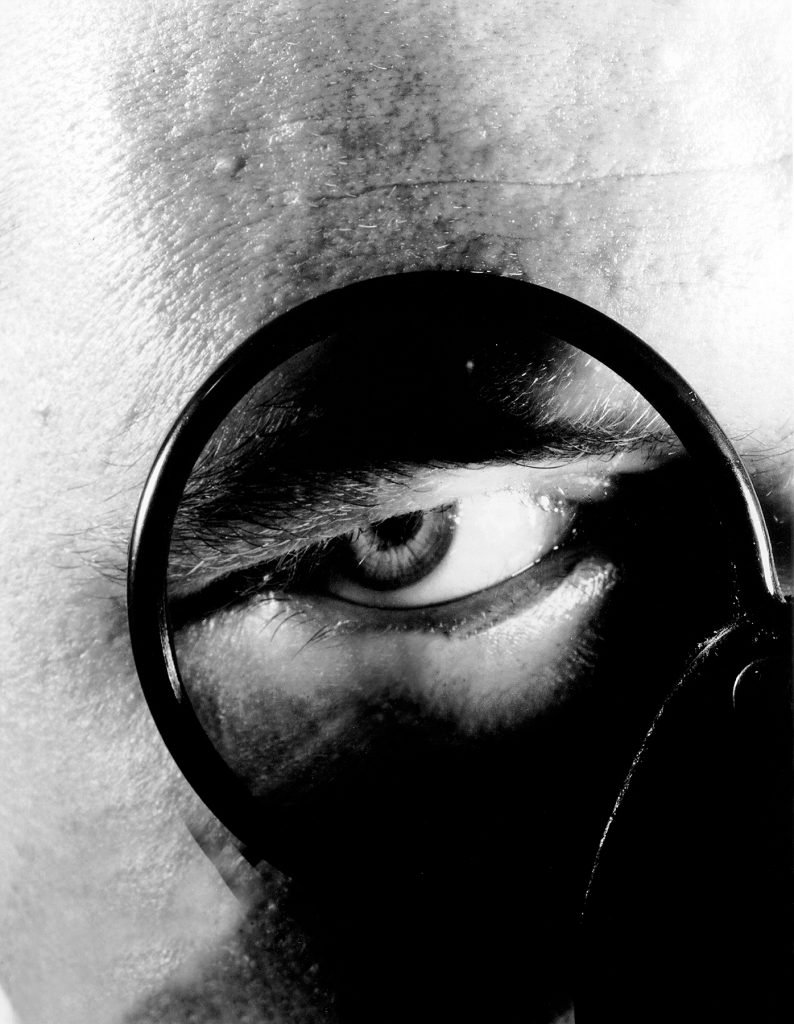

The work I’ve made for the ING Unseen Talent Award is a visual study into the language of lying and finding commonalities through gesture and visual cues. I created a fictional study on lying and whether it could be something that could be categorically defined – something we could recognize immediately as an untruth. A lie is a false statement, which has the intention of creating a false image. Visually, I was really interested in how to create a false image, something that can be read or misread in multiple ways.

GC: What better of photography to investigate a visual lie. A medium that has an historical relationship with deception; I think about the use of photography during the moon landing or the one made by politicians to represent themselves in a certain way… an issue that is very important in these years due to the extensive use of photography, a global language that has to tell an idea rather than reality. Where did the idea of working on these issues come from?

AL: It’s been quite a natural progression. My previous series ‘The Meteorite Hunter’ saw me develop an interest in perceptions and how the context of imagery changes people’s perceptions. This led me into thinking about truthfulness in photography and how our perceptions could be altered. It’s an interesting idea about photography presenting an idea rather than a reality. My work functions in this way entirely and I’m much more interested in thinking about photography as a means of interpretation rather than representation.

Photography is problematic when thinking about ideas of representation, as it’s hard to separate a photograph from its author and any agendas connected to why it’s being taken.

Within my own work I look at how images can be manipulated either in the way they’re presented or the context of how they’re read. It becomes about questioning how we see and challenging us to think about what’s in front of us.

By this I mean taking part in the process – letting yourself be lead around an image, and questioning what starts to happen when you make a series of decisions. If you’re faced with a missing area of a photograph, you either fill in that space or you’re confronted with your own frustrations at not being able to see what lies behind it. The process your brain goes through interests me, as that’s the point when you consider what you’re seeing and what you perceive of that.

GC: You talk about a visual code that could be understood and ultimately mastered, what would it mean to be able to understand lies in the same way that you understand a mathematical problem by knowing its data?

AL: I think it would have a huge impact. Imagine if we could know something was a lie as it was told to us. It would change everything, politics, the news, our relationships… we would read situations completely differently. I’m sure it would have it’s own issues though and I suspect it wouldn’t be too long before a new form of deception and manipulation would evolve.

GC: Your previous series, “Other Ways of Knowing”, is an exploration into the illusion of magic and misdirection in comparison to ideas of hoax, deceit, and trickery. A different kind of illusion, based on different strategies. What are the main differences compared to the deception of “The Path Of An Honest Man”?

AL: I think of these two works as brother and sister as I made ‘The Path of an Honest Man’ while I was still in the process of making ‘Other Ways of Knowing’ so they’re heavily influenced by each other. For me, ‘Other Ways of Knowing’ focuses on looking at the idea of deception from the audience’s point of view. We take part in the performance and are fooled to a certain extent. ‘The Path of an Honest Man’ is much more focused on the idea of the deception so it becomes a comparison of these viewpoints.

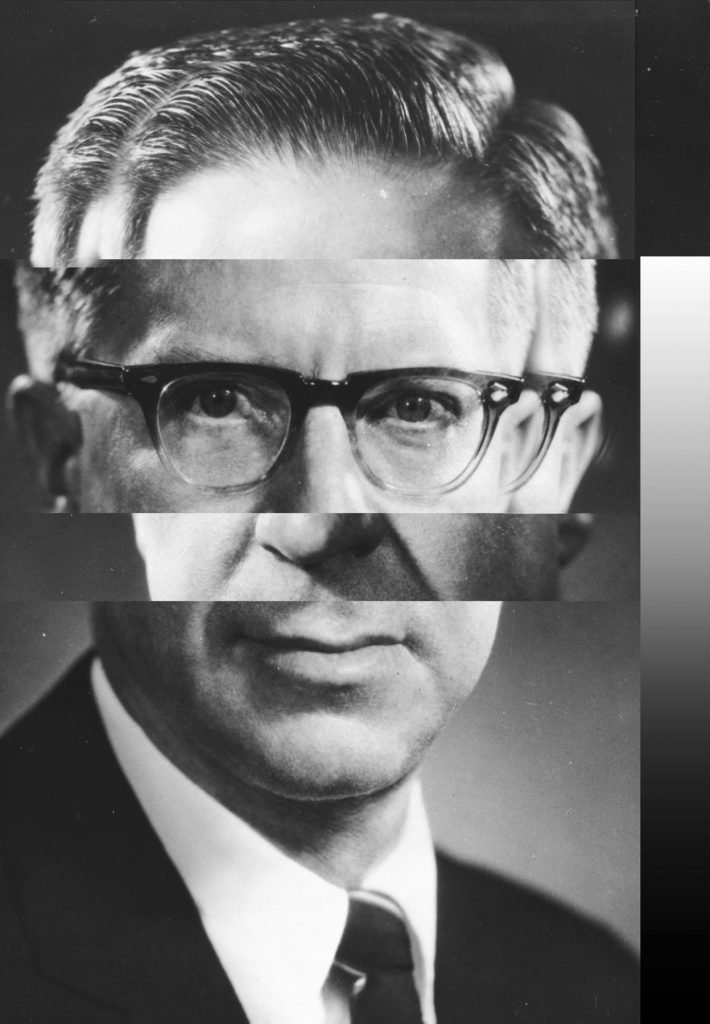

GC: Your own work of scanning pre-existing images can be defined as an illusion, you make these images a means to convey a completely different concept from the original one, don’t you agree?

AL: My main reason for using found imagery and then intervening with them is an attempt to change their narrative and bring them in line with the ideas I’m looking at. Although, I hadn’t considered them as an illusion so that’s an interesting idea. I guess it depends if you’re think about them in their original context or their new one – are they illusions of the original images or entirely new images with different functions?

GC: You have an almost psychological approach to this matter, the analysis of the connection between seeing and the cognitive process aimed at creating a moment of hesitation. Have you ever had the opinion of a psychologist about your research?

AL: I haven’t although I’m always reaching out to scientists to try and learn more. For me the factual research element of my work let’s me root that in fact, meaning I can be very experimental and playful in how I make the images. I really need that balance to make my work. In the future, I’d love to do a more collaborate project alongside a psychologist or scientist and see what the outcome is.

GC: How do you think your work will evolve?

AL: I suspect I’ll go further into the science and possibly further away from the traditional aspects of photography. I’m open to any form or medium that helps me present my ideas and all the directions that could take me in. I could speculate but ultimately I don’t know what that will look like, which is part of the excitement of it.

GC: After your B.A. you worked for Joel Meyerowitz, what kind of experience was it?

AL: It was an incredible time. Learning from someone with that much experience and wisdom was truly an honor. He’s also one of the nicest people I’ve ever met so all in all, a really amazing experience.

GC: And now, what are your plans?

AL: I’m planning a few exhibitions for later this year and the earlier part of next year. I want to experiment with using screens in my installations, so I’m trying to get sponsorship for that at the moment. I have a few new ideas so I’m also in the process of making new work.

Alexandra Lethbridge (b.1987) is a photographer born in Hong Kong and based in the UK. She graduated from the University of Brighton with a Masters in Photography. Previous education has included Winchester School of Art, UK and the International Center of Photography in New York.

Found photographs, archival imagery and constructed images of her own making form the basis of Alexandra Lethbridge’s research-based practice. Drawing upon a range of references and source material, she combines scientific theories with fictional constructed images, bringing them together as a form of storytelling. Approaching image making in a playful and experimental way, her practice deliberately mixes fact and fiction to create expanded views of the subject matter she explores.